The Making of a Widower.

On Life After Losing Our Person.

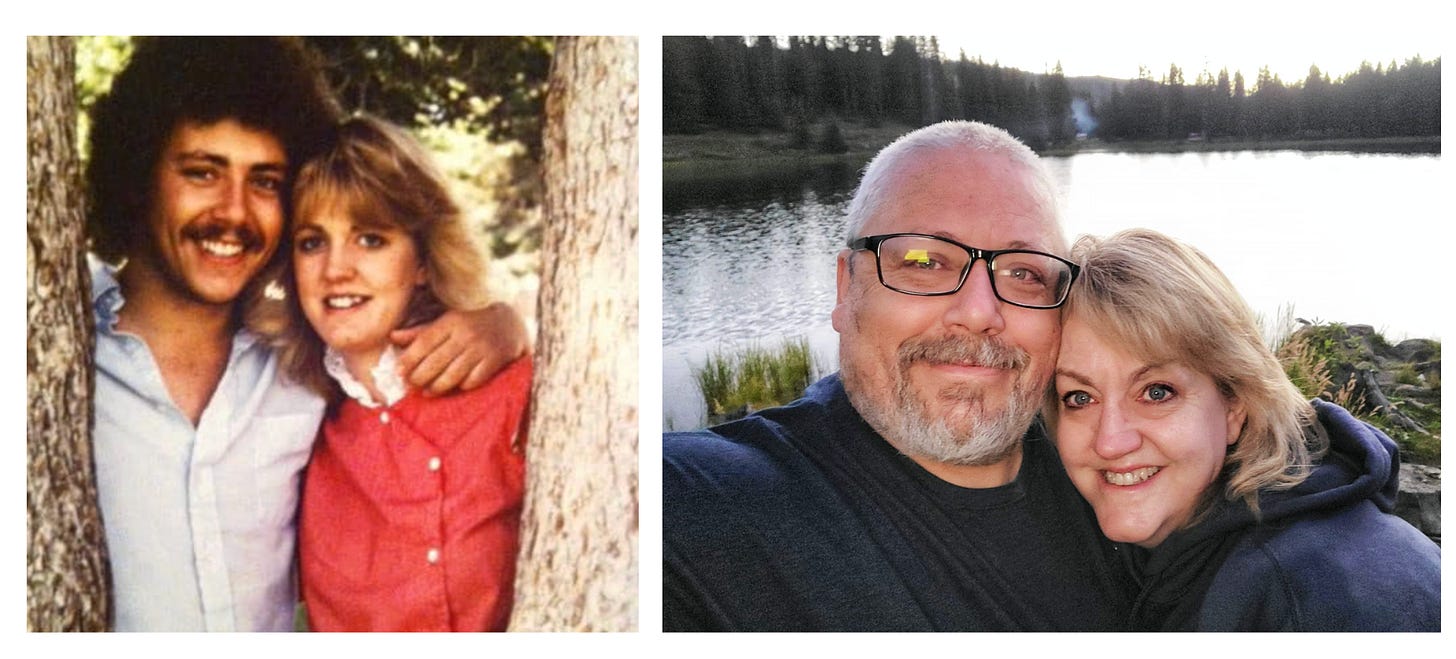

A few months ago, I asked my dear friend, Scott Dickensheets, to write an essay about the absolute worst thing that had ever happened to him. This was incredibly unfair. Laura, the love of his life for four decades, hadn’t been gone a year and here I was asking him to write about what life was like without her.

I had two covert reasons for asking:

First, Scott is living my nightmare. I, like Scott, have banked on being the first to go. It’s so weird how we just decide that, like we have control or something. (We are dumb.) Losing David is my big fear and this took shape in my brain after his heart attack. Who would I be without him and our relationship? Who would our family be without him? How could I fill in all the blank spaces he would leave behind? How would we live in those spaces and fill them? How would all of us ever recover? And then how bad would it be if we actually did recover? How would I plow through all the accounting alone - his business finances are complicated - and who would load the dishwasher so the dishes were placed into the racks just so? Like, just so in the most anal way possible? I knew Scott would grapple with all this, both emotionally and practically, macro and micro. And he did, so beautifully and achingly.

Second, Scott is a writer’s writer. A world-class writer and editor who was, at one time, my editor on a piece that launched this leg of my career as an essayist. Scott has written and edited everywhere. And it shows. I could ask very few people to take on writing intimately about death and loss. Newbies might have the will, but not the chops. Scott’s writing has elegance and depth and maturity and self-awareness and restraint and vividness. He is both wry and devastating in equal measure.

I have been wearing his essay since he sent it. I have broken down and had to compose myself in the bathroom. I find myself re-reading lines and committing them to memory. What he has made me realize is this: No matter what losses we are forced to endure, no matter how unfair and stolen it all feels when we lose, the gift is that we got to have this kind of love at all. It is not a given for any of us.

What I hoped is that by writing this - like most writers, writing is a way to know ourselves and the world - Scott could wrangle some more of this grief. Clarify it. Maybe take the next baby step. I hoped my request would be a balm. And an excuse to revel in Laura one more time.

I hope you will welcome my friend, Scott, to The Great Perhaps. I’m including his essay below. Please feel free to comment and share and I’ll have Scott show up in comments. And maybe encourage him to write a regular newsletter? Of course, I always want to hear your experiences.

Thank you, as always, for reading. xo Kim

______________

My wife died a year ago. I’m 63, and this blunt, immersive, ongoing truth will radically reshape the years I have left. I had just retired in April 2024 when the pain in Laura’s back turned out to be a pancreatic nerve tumor, first misdiagnosed as benign, then eventually deemed cancerous and inoperable. Five months later, a week after our 39th anniversary, my soulmate was gone.

I can’t possibly tell you all the ways I haven’t recovered, and I don’t just mean the sudden tearbursts I still experience. I no longer sleep in our bedroom, now haunted by her final days in home hospice care, where she slipped away as I held her hand. Anything she bought and handled, however small or offhand, I have a hard time throwing away. I may never be able to sell this house because it would mean parting with the gorgeous hummingbird mural Laura commissioned for our backyard, an image now so richly evocative of her. I spend whole days frozen in bewildered stasis, unsure what to do with my life — my future plans were really our plans, and they’re gone. I could go on.

Physically, the health challenges that go along with reaching retirement age badly out of shape are worsened by depression: junk sleep; grief spikes that manifest as chest-tightening panic attacks; too many interludes of mental and emotional listlessness, now especially scary as I age toward a heightened likelihood of Alzheimer’s. Things I once enjoyed often barely interest me now. (Hopefully I’ll get to you someday, nightstand reading pile.) Yes, I’m capable of joy, of course I am, but it’s usually short-lived and freighted with guilt — too much feels like a betrayal of our lifetime bond, which remains in effect. How are you doing, someone texted the other day. Healing by the centimeter, I responded. My thumbs believed it when they typed it, but I rarely feel that certain.

The trick I’m trying to learn now is how to live with the grief, to accommodate it somehow, rather than just responding to its triggering. I’ll let you know when I have something on that.

Shortly before her illness and its treatment made communication difficult, Laura looked up at me from her hospital bed, eyes wide. “I don’t want to go without you,” she whispered. “And I don’t want to stay without you,” I whispered back.

But here I am.

***

To be sure, there’s more to her loss than this miasmic sorrow. I still must operate my daily life as a solo act. It sounds stupid to say this now, but I always blithely assumed I’d die first — my shitty diet and sedentary lifestyle have always argued against longevity — and this matters now because I frankly never even imagined the true contingencies of life without Laura’s wisdom and sharp focus.

One of the deflating realities of widowerhood was realizing one day that I am no longer the most important person in anyone’s life. I’m no one’s primary concern. You just don’t grasp what a bedrock feature of your life together it is to know someone is focused wholeheartedly on you, and you on them. Yes, I have a big family, three sons, their partners, nine grandkids in all, and they all have absolutely backstopped me at every point, as I have tried to do for them. But I’m a second-order concern in their lives, which is as it should be. But it can be a lonely, disorienting feeling.

Nonetheless, her absence has as many practical implications as emotional ones. Keeping the household going, for instance. The attention to detail and knack for big-picture thinking that made Laura a terrific elementary school principal paid off at home, too. She handled all of the family math: paying the bills, doing what I called “bank stuff,” calculating interest rates, managing our credit, understanding the role a county assessor plays in our lives. This was a primary example of our yin-yang compatability: Pragmatic, organized, and gifted at real-life problem-solving, she assumed this role naturally, as I am none of those things. I suck at math.

But now I have to be those things anyway, and not just for my own benefit. My youngest son and his family live here, too, two more generations of Dickensheetses depending on me to wrangle all the unfamiliar but necessary facets of homeownership — budgeting, mortgage, maintenance, taxes. I’ve had to learn it all from scratch, and without any guidance from Laura; the last thing she needed in her final stretch was to walk me through the mysteries of online banking.

You pull a lot of G’s on a learning curve that steep, and I was frequently dizzied by questions like, Who holds our mortgage nowadays, and how do I pay it? Where’s our 2023 tax paperwork? Are we still paying into our local improvement district? It’s frustrating to be rendered so thoroughly bewildered by something so important at this stage of life. You learn, of course, but it’s difficult while also trudging upstream against the grief that’s draining your reserves.

And everything was further complicated by business systems optimized for their own convenience rather than ours. After Laura died, each of our joint banking, credit, and other accounts had to be canceled — sometimes without notice — and reinstated as single accounts, always with the maximum freakshow of red tape, inscrutable phone trees, death certificates, signatures, and notaries.

Without my wife to consult about these indignities, I’m lucky that our middle son inherited his mother’s calm, clarity and head for numbers, and is a homeowner himself. He schooled me as well as he could, and it’s been enough to get by; I still have the house and am not quagmired in new debt. I belatedly regret all 39 years of deferring this stuff to Laura, not only because it left me unprepared to handle it, but because, in actually handling it, I’ve gotten a truer sense of how much she had to deal with. It wasn’t fair, no matter how willingly or cheerfully she took it on. I’m sorry, babe.

However, she did something that did help me immeasurably after she died, a singular gift that I offer now as an actionable takeaway from this essay, particularly if you’re the family-math person in your home. She paid a little extra on our bills. Not in the beginning; hell, I was making $250 a week when we got married, and we had our share of shut-off utilities those first few years.

But at some point, she began overpaying the power, gas, water, and trash bills by a few bucks here and there. Each billing cycle, apparently. She mentioned she was doing this once or twice, but I never grasped the scale of it until those duties fell to me. She’d built up massive credit buffers with every utility. I didn’t pay a single power bill between the spring of 2024 and this June, when the last of our credits ran out. I still haven’t paid gas, trash, water and sewage, or internet. I still have more than $1,000 credit with some of them. How long had she been doing this? I’ll never know.

But what a gift! You can’t fathom how much it cools your grief-lashed anxiety to be able to start putting your life back together without being nagged by bill collectors. I had the time to figure out online banking myself. This one small move put the grace in grace period, and everyone who hears that story agrees: That’s so Laura. If there’s one thing everyone knew about her, besides her fierce love of family, it was her deep, thoughtful kindness. To know her was to receive small, unexpected gifts all the time.

I still have plenty of blind spots, but I’m picking them off one by one. For example, it occurs to me as I write this that I still don’t know what a FICA score is, or whether I even need to know at this stage. Note to self.

Meanwhile, my future remains to be sorted out. Our retirement plans — travel, new experiences, joint hobbies — seem beside the point now. Yet I remain retired, with all the free time that entails. As I’m among the first of my friendship circle to leave the workforce, and my kids are all employed, my time is generally my own. I do some freelance writing, which I’d always intended to do, and I read when I can rouse my interest in it. But that leaves a lot of hours, many of them listless. Trying new hobbies sounds like a good idea, but I’m only now realizing that without Laura to share stories of my progress with, that idea is a bit less appealing.

***

I still haven’t come to terms with the word widower, and the many gradations of aloneness it contains.

As the doctor left her hospital room, having just delivered what amounted to her death sentence, Laura sat up in her bed, shrugged, and said to me, “I guess we’ll have to start shopping for your next wife.” Not, as you might imagine, what I expected. While she always appreciated a bawdy joke, Laura wasn’t given to gallows humor. But then, she’d never been on the gallows before.

Still, after four decades of deep intimacy, I knew what she was getting at: Yes, she wanted to signal permission for me to someday move on with my life — but quivering at the heart of it was one of her worst fears, of being forgotten, of failing to continue mattering, of being left behind not only physically but in the grand narrative of this amazing family we created.

This is impossible, of course, and I like to think that deep down she knew that.

An anecdote:

Late one night some years ago there came a sudden crashing in our master bathroom. Still deep in my REM sleep, I nonetheless shot out my left hand to determine whether Laura was still in bed. She was, thank goodness. (The noise was the cat doing cat things.) She found it exceptionally sweet that my instinctive, preconscious reaction to a scary noise was to make sure it didn’t involve her.

She was right, too; it was sweet. But it was also ordinary. Indeed, any time in the night I woke up, I gently touched her – for comfort, for reassurance, probably because I couldn’t believe my luck. She did the same, even – because I’m a shallow breather – taking time to make sure I was still alive.

Not surprisingly, we were champion hand-holders, and, as I assume most couples do, we developed an elaborate inventory of touches, tickles, shoulder rubs, light pinches. I haven’t lost that urge to touch her, to randomly connect. Her urn sits near the desk in my home office, and every morning I tickle its surface the way I did the small of her back as she stood at the mirror applying makeup, and I say, as I did then, “Good morning, babe.”

Point being, she remains woven into my life practically at the molecular level, and she, of course, knew this. That if and when I move on, I’ll be taking her with me. For now, I can’t imagine moving on. I can’t picture a time when she won’t be a vivid, out-front presence in my life. All this time later, I still find myself wanting to forward her a meme, text some family gossip, turn to blab about something I’d just read, eaten, or thought. While the year since she died has been full of big, heartbreaking reminders of her absence, that nanosecond pop of utter loneliness — when my sudden urge to connect with her is shot down by the truth that I can’t — may be the most bottomless feeling I know.

As I write this, we’ve just marked the one-year anniversary of her death, our close-knit family celebrating the woman who did the knitting by enjoying her favorite comfort food — tomato soup and grilled cheese sandwiches — and the solace of being together. That morning I paid for the Grouchy John’s mobile coffee truck to visit her old school, where a mural in her honor adorns a wall; a small gesture of healing to her beloved former staff. Tributes to her huge and generous heart appeared on social media and arrived by text and email, testament to her enduring impact in this life. One of her oldest friends wrote to me, her sorrow palpable: “She was so big.”

Yes. Yes, she was. And so is the space she left behind. All we can do now is fill it with kindness in her memory.

It does get easier with time , I promise . My husband and I were together 47 years . He died of chronic leukemia a few years ago. We divided chores. He didn’t know anything about mine , and I didn’t have a clue

about cars, cooking and finances . I manage the finances now, not easy ( he didn’t have life insurance )

I still don’t know about cars, and I walk past the stove and I talk to him; “ See, I didn’t make it dirty, I didn’t turn it on . But what you really need to do for yourself is to start walking.

Map out different loops ! That will protect you from Alzheimer’s and get you in shape . It’s a form of meditation

You’ll never forget anything . I walk 6 miles every day morning and I’m due for a knee replacement .

Susan

That was so moving. My husband came to bed and I was reading it a second time to him. He hmmmed a few times, and chuckled once because of the similarities most couples share. Then when I was almost finished I looked over and he was asleep. He falls asleep to the comfort of my voice. It’s so hard to imagine who will I share my evening thoughts with if he goes before me. Who is going to listen to my “ how is this even possible” questions of the day. One of the most scary things you said was “I’m no one’s first concern”. I always know that I am truly G-ds first concern. I pray that carries me through and I pray it will for you also.