The first nearly 40 years of my life, without marriage or children, with a body not stretched to its biological limits or taxed by longevity, I led a pretty visible life. So the first time, I realized I could be invisible, it came to me as a heady experience.

I was in my third trimester. My belly finally popped, roomy and visible. It was 2004. I was 39. David and I had known each other a bit longer than the pregnancy, by a couple months. Everything was new.

I had written soap operas when they were a thing, and David had become friends with soap star Ricky Paull Goldin. We were out one night in NYC and I found myself off to the side talking to Ricky, while David chatted with his then girlfriend. I adjusted my body language so she wouldn’t worry that I might be coming on to her boyfriend. I was used to making these little adjustments unconsciously. I put space between us so he wouldn’t misinterpret my attention. I didn’t laugh loudly. Touch my hair. I kept my hands crossed in front of me, instead of wildly gesticulating and emoting everywhere, as is my natural state. I didn’t squeeze his hand in reaction to something touching he said. I didn’t think about these things through exactly. I knew that misinterpretation could happen at anytime, because it did. A man could easily mistake a smile or laughing at a joke as attraction to him. It happened all the time. A woman’s body can be a canvas where other people, Jackson Pollock like, throw their projections about themselves onto us.

But none of this was necessary. Because I was no longer fuck-able.

The girlfriend was unphased. David barely noticed, and Ricky saw me as the soft, open nurturer, giver of life, maker of organs and soft tissue that pregnancy embues. We spent the conversation talking about his hope to become a dad. I was, for the first time in memory, invisible as an autonomous adult being. Overnight, I represented the soft hues of caregiving. Safe. Non-threatening. Non-sexual.

Weirdly, it was an anectodote to being constantly sexualized that I needed. I liked invisibilty.

But there are different grades and implications for invisibility. I know the only reason I don’t feel invisble these days is because I’m still under 60. And David and my family buffer it. They see me. I am a sexual being to David, a love interest. Still fuckable to him. I am more to him than the mother of his children. I am seen as a creative professional, a competent person, a human with ideas. I am given respect. I have agency. I move around the world feeling that. I am still a player in the capitalist system. I am white and thin. I have proximity to youth and youth privilege. We are not poor. My mental illnesses have been tamed and made manageable by drugs and therapy. I have a doctor who listens to me. I am critical in the day-to-day to my adult and juvenile children, who still need us practically, financially and psychic-ly. And so I am seen, and this is enough. The public gaze matters less to me right now at the end of my 50’s.

But I know that is not the experience of many older people, particularly women. I hear from them here on this newsletter.

Feeling invisible is one of the great challenges for women as we age. It can and does happen to many of us as we lose family and friends, become more isolated, leave jobs and the capitalist structure, become less mobile, less sexually invested, move further away from youth-privilege, experience being less-able bodied, less brain competence, less financially viable, and more diseased. The more the effects of aging impact us, the greater the chances that a lot of us will find ourselves more outside of our cultural references, companionship and relevance.

And make no mistake: both men and women feel it. But today, I’m going to focus primarily on women.

A 2023 English study took on the issue of visibility in women. The study gathered 158 mostly white (about 6% POC) heterosexual, lesbian and bisexual, ages 50 to 89 and asked them about their life experiences in the UK.

Researchers Found Five Dominating Categories of Visibility Issues:

1. Being under-seen/mis-seen in the media

This has improved some with TV shows like Hacks, Murders in the Building, Man on the Inside, and Grace and Frankie. Movies, too, now feature older actors, like Meryl Streep, Nicole Kidman, and Emma Thompson. In the making of the Kathy Bates’ new show, Matlock, the writing is specifically geared to tackling the issues of invisibility and the plot plays with these tropes.

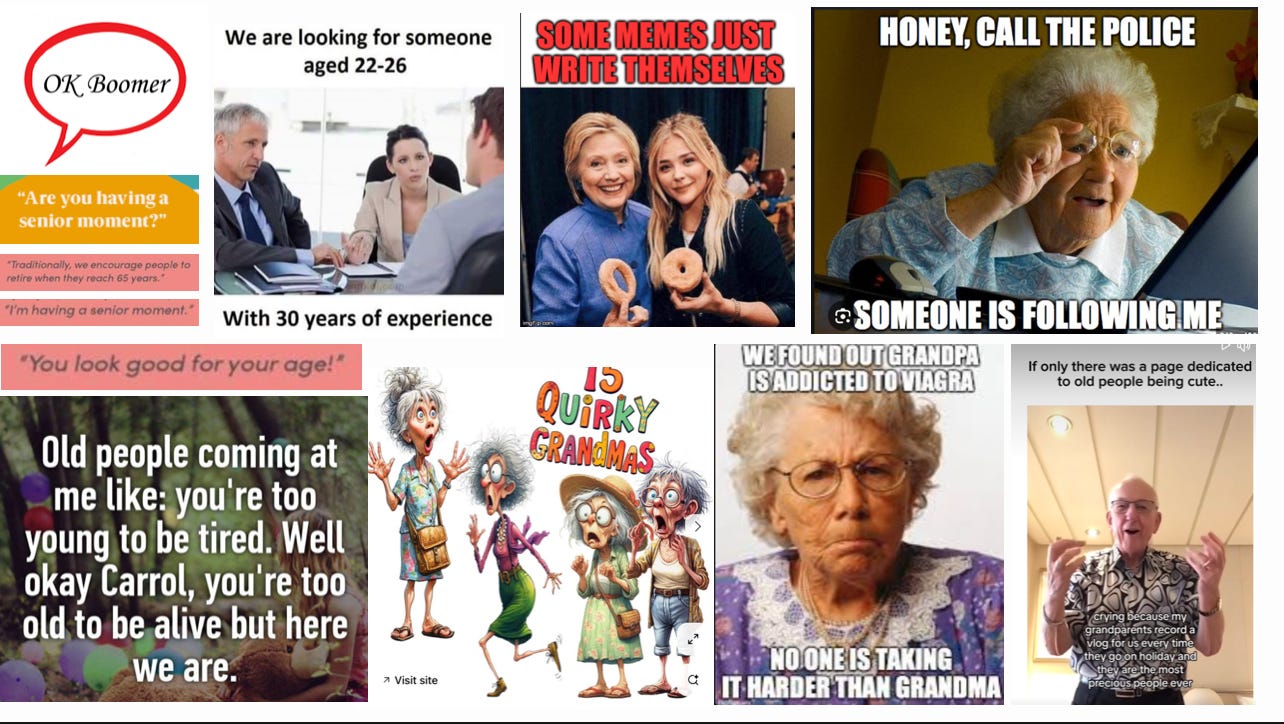

Despite some shifts to meet the moment, and the new attention around menopause, a trip to the greeting card section and a gander at memes on the internet tell us that ageism is all around us. (Ageism also extends to children and youth, and I think it might even be more crucial for them, but today, I’ll just be tackling issues around older people.)

A 2024 study in Gerontologist found that ageism was rampant in greeting cards for people ages 30-60, illustrating a fear and contempt for aging. Older women are perceived as frumpy. Their bodies are lumpy and sagging. They wear house dresses and are cranky. They yell at people. They exist outside of the culture, unaware of cool.

With memes, another study found that older people were often portrayed as immature, child-like, less intelligent, blundering, and emphasized their dependence on other people. Older people were perceived as unsophisticated and not being up on cultural references. The Look at them now! pages advertised all over social media as click bait, are fraught with once-young viral celebrities now aged, with cellulite, bulges, out of control bodies and faces caught without makeup or flattering lighting.

The idea is to disrobe the perception of youth and shock the audience with the ugliness of exposed aging bodies.

2. Being mis-seen as objects of sexual un-desirability

We are either straight predatory cougars, luring in the younger men by stepping outside of the expectations for our age - a common older actress part these days - or we are asexual. Or we are older lesbians and bisexuals, ignored into obsolence in the patriarchy, because of a lack of proximity to men’s sexuality. This is important because invisibility makes it easier to discriminate against already-marginalized groups and makes it harder for those communities to find each other and advocate in numbers that can make real change.

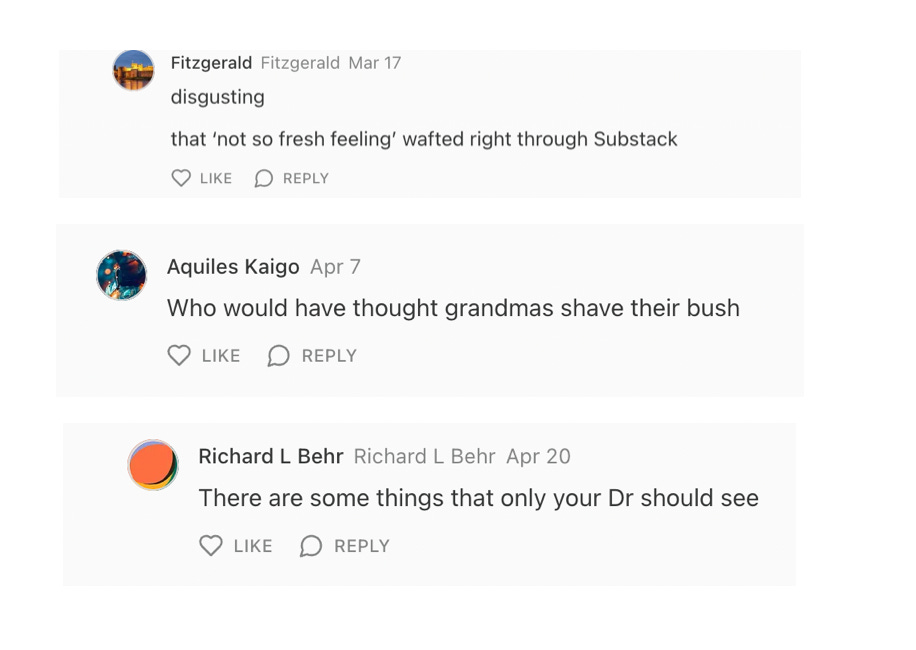

If you look at some of the comments on my viral On Getting Old essay, which features Aleah Chapin’s series of beautiful naked older women, you can see that a few people were uncomfortable with women’s nudity; older women cavorting naked and playing together. No shame, no hiding, removing all insinuations of sexualness and just being joyful. Again, the women might be fuck-able, but what they are selling in the art is not about men’s sexuality. It’s about their own personal freedom.

Most of the comments were beautiful and affirming. But not all.

A cousin to this form of invisibility issue is the you look great for your age trope, which is both patronizing and really more about complimenting us for our proximity to youth or for winning a kind of genetic lottery. It implies that there is something wrong with being a certain age and looking like that age.

One study participant, a 59-year-old heterosexual white woman, wrote:

It feels like it is about “fuck-ability”—if men don’t want to, then that seems to be “our fault” for being old and unattractive. Then we become invisible. Add in other characteristics that intersect with desirability—like race (young black women are fetishized, older black women are not) or disability.) This then gets taken on by women who get caught up in the desirability game, where they contrast their own desirability against older women, and the fear that they, then will become those older women one day.

3. Being “ignored” in consumer, social and public spaces

This category can be summed up by this comment from a 77-year-old British lesbian who wrote: I was in a queue for a rail ticket and an impatient, young traveller in the queue said “You people shouldn’t be travelling at this time. We have to get to work.”

This is like suggesting that people in upper level social-economies shouldn’t grocery shop on SNAP day because they are rich enough to shop anytime, not just on the days when poorer folks benefits come in. Imagine the outrage if someone suggested that? The idea that some people should and shouldn’t exist in public spaces is at the core of pushing people into invisibility.

The othering of older women happens often in public spaces. Older women report being talked over by sales people, ignored trying to order a drink at a bar, having to wait for long periods at restaurants, pushed aside in lines and having people butt in front of them, as if they were literally invisible.

A 75-year-old lesbian in the study writes about being in a meeting, being ignored and then watching a younger person say exactly the same thing and get full credit for it. I think this is what the artist, Deborah Wood’s street art captures; the utter rage at being under-utilized, under-seen, under-acknowledged in places where we once commanded attention and access. There is a loss. And then in contrast, with her dancing ladies in tutus, being free and open and not apologizing for taking up space.

Invisibility for my cohort is no joke, Woods writes in the Guardian. It’s actually dangerous. It leads to exclusion from the workforce, financial precariousness, growing homelessness, bad health outcomes, elder abuse and silence and inaction in social policy.

This is magnified when the older person is disabled. Participants talked about people coming to visit them and having their caregivers intercede on their behalf at the door, instead of allowing them to have agency over who visits and when. And then this from a 73-year-old, queer British woman:

My partner is disabled. When she was younger people in general were sympathetic and helpful, but now she’s older they seem to have less patience, as though it’s just part of ageing and something they prefer not to think about.

Older people are visual reminders of human mortality. Proof that there is an end and the end is not always easy or pretty. It is easier to keep us under wraps.

4. Being seen only (often incorrectly) as a grandmother-type

You don’t have to be an actual grandmother to catch this stereotype. The assumption is clear. If you are an older woman, you still need to be tied to childbearing in some way because it is from a societal perspective, our primary gig.

A 76-year-old British lesbian in the study wrote: I went to book a flight to North America to speak at a conference. Travel agent not only assumed I was going to visit my children/grandchildren—why else would an old woman travel?—but continued to assert that, even after I told her I wasn’t! Not only invisible, also un-listened to!

Making someone into a grandma is similar to the experience I had when I was pregnant. You represent the non-threatening life giver. People have grandmas and know how to relate to them. They are sweet and have hankies in their pocket books and caramels in their pockets. There is something soothing about the idealized grandma trope, always a giver, never with her own agency, and so it is a lazy trope.

5. Being patronized and seen erroneously as incompetent.

What can we get you, young lady? Do you know how to use email? Do you know how to work the microwave? The way we say: Awww, they are so cute when we see older people holding hands or kissing. Or bless her heart uttered when an older woman is doing something adventurous like ziplining over a jungle canopy. This also includes speaking to older people in a sing-songy voice, as if they are children or speaking loudly or talking about them in front of them, because we think they can’t cognitively understand us.

One queer white British woman in her 70’s told the story of breaking her arm when her dog took off on the leash. At the hospital, the staff referred to her as an elderly lady who’s had a fall. She went from having an accident to being marked as frail and elderly, which made her feel, well, frail and elderly. Another British bisexual woman, age 65 talked about being at physio appointment. While her goals were regaining full mobility, her physician was focused on her being mobile enough to pop down to the local shops.

The implications for invisibility, for having so much distance from fuckability, are not frivolous. They can be catastrophic.

Last week, in the comments of my essay on Aging (Dis)Gracefully, a woman named Trece wrote this:

Imagine being 73, weighing about 280 at a height that has shrunk to 5', confined to bed, and wearing a diaper. Living on Cheerios and pb&j, because the food is so gross. Husband who stops in monthly just to bring me my mail.

That's invisible and without value.

And yet my mind is as clear as ever.

This piece about invisibility is for Trece, who put her story out there. Brave shit.

And for the people like Tara, who responded. She worked in longterm care faciltities in Trece’s area, and was able to offer her some options. Hope. Essentially, making Trece seen with her response.

The antidotes for solving these big issues are always complex. The challenges are entrenched. Public policy is a bear. But there is a lot we can do on the ground. We can show up loud in the world and be ourselves, without shame. We can find the courage to say our truths, our stories, outloud. And we can shine some of our light on other people, making those who are invisible, visible. Unapologetically.

Thank you, as always, for reading. xo Kim

How to put this without sounding like an asshole - I used to get a lot of attention from men. Most of it benign and I enjoyed it. Nothing big just appreciative looks, winks, bartenders buying me drinks, etc. I never felt threatened or like anything was expected of me. I am 99% at peace with the fact that this doesn't happen much anymore. Not because I've "lost my looks" but because I'm 54. What I find is I have to remind myself periodically that NO ONE IS LOOKING AT ME. I'm worried that my shirt is sweated through at the gym but really no one is looking at me. I didn't put make up on to go to the store and no one is looking at me. I find it pretty freeing actually. But occasionally I miss being the pretty young thing. It's to your credit Kim and your writing that I am sharing this, something I would normally NEVER admit to, let alone in writing!

I became invisible or unfuckable recently. Since I got my 1st flowers delivered at 4, leered at by a much older guys at 12 - I am good with it. Hell I'm estatic. I'm 76 and only recently started to age, wrinkle. No surgery, baked in the sun - just good genes. Thanks Mom & Dad.

I have a light weight mobility scooter that goes fast, I love it and now "Scootie" gets all the attention. All males 50 & under are fascinated with it..

Funny.