Are You Afraid to Die?

Grappling with death anxiety, while still healthy (ish) and young (ish).

I live with a certain degree of denial that comes from having been, more-or-less healthy, my whole life. I had a brain tumor removed in 2001 but other than that, I - so far, knock on wood - have won the healthy-ish lottery. Aches and pains, intense perimenopause symptoms, but I’ve been mostly lucky.

Just a few weeks ago, in a booth at our favorite date night bar (Red Dwarf, for you Vegas folks) I leaned in close and confessed to my husband, David, something he probably already knew.

I don’t actually think I’m going to die.

I pulled back to read his face. He wasn’t entirely shocked. He knows my denial well. The lies I comfort myself with. Sue me, it’s a coping strategy. LOL. Like I might be in my last year of my 50’s this year, but I’m also not a day over 40, right? David allows it, as good partners do, and then laughs at me when I’m revealed to myself.

I entertain him.

Okay I knew I’d die, I explained to him. But I didn’t think that time would actually come, because in my mind it was decades away, like I was on one of those autowalks - the flat escalators in airports - running into the future, which I can see in front of me, but waaaaaaay out there and always unreachable. The autowalk keeps going, and the future is out there, the end is out there. I never get there.

I also thought I might die young. Like a meteor would hit me and I’d be gone. No need to think about what it means to leave the earth or to be here, because it was either going to happen suddenly, and without warning or consent, or it would happen, but in some mysterious place and time that was far away, and I could push it away and never have to consider it.

When I was a little girl, a morbid anxious little girl who thought about these things late into sleepless nights, I decided that the best way to die would be in a catastrophic explosion, just burst apart in an epic evisceration. No idea it was coming and no idea it had ended, I craved to not have to grapple with losing and loss. An evisceration meant I didn’t have to know or think about the end, or be at peace with it, or in an abyss with it.

I wanted to avoid what my dear friend, Scott and his wife, Laura went through with her cancer and their ultimate loss. She said: I don’t want to go without you. And he said back to her: I don’t want to stay without you. This seems like the ultimate hell. I do everything I can to push that as far away as possible.

Can’t David and I just be eviscerated together without notice??????

Lately, I’ve been considering death more expansively, taking into consideration that I might not be eviscerated, and might have to deal with the news, tell my family, plan the end. Maybe I will be taken before I’m ready, is anyone ready? How do you get ready, when we are so focused on life and living? Should I stop my living to consider death? Or make living about tricking death?

In the last year of my 50’s, I wonder how much the anxiety of the limited time ahead, which has always been there and has always been limited, plays into how I make plans now, and what I want my life to be as I grow into this last third of life.

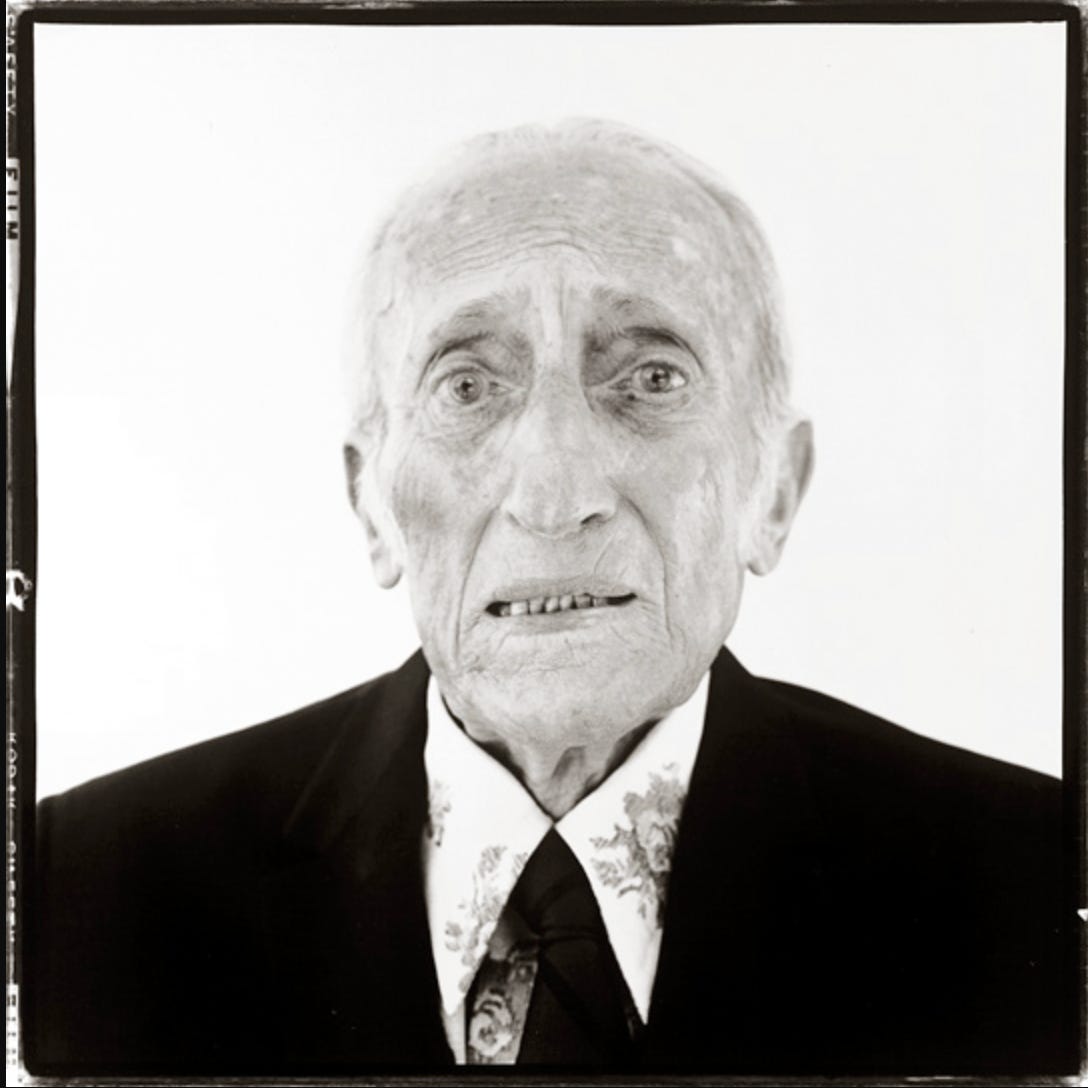

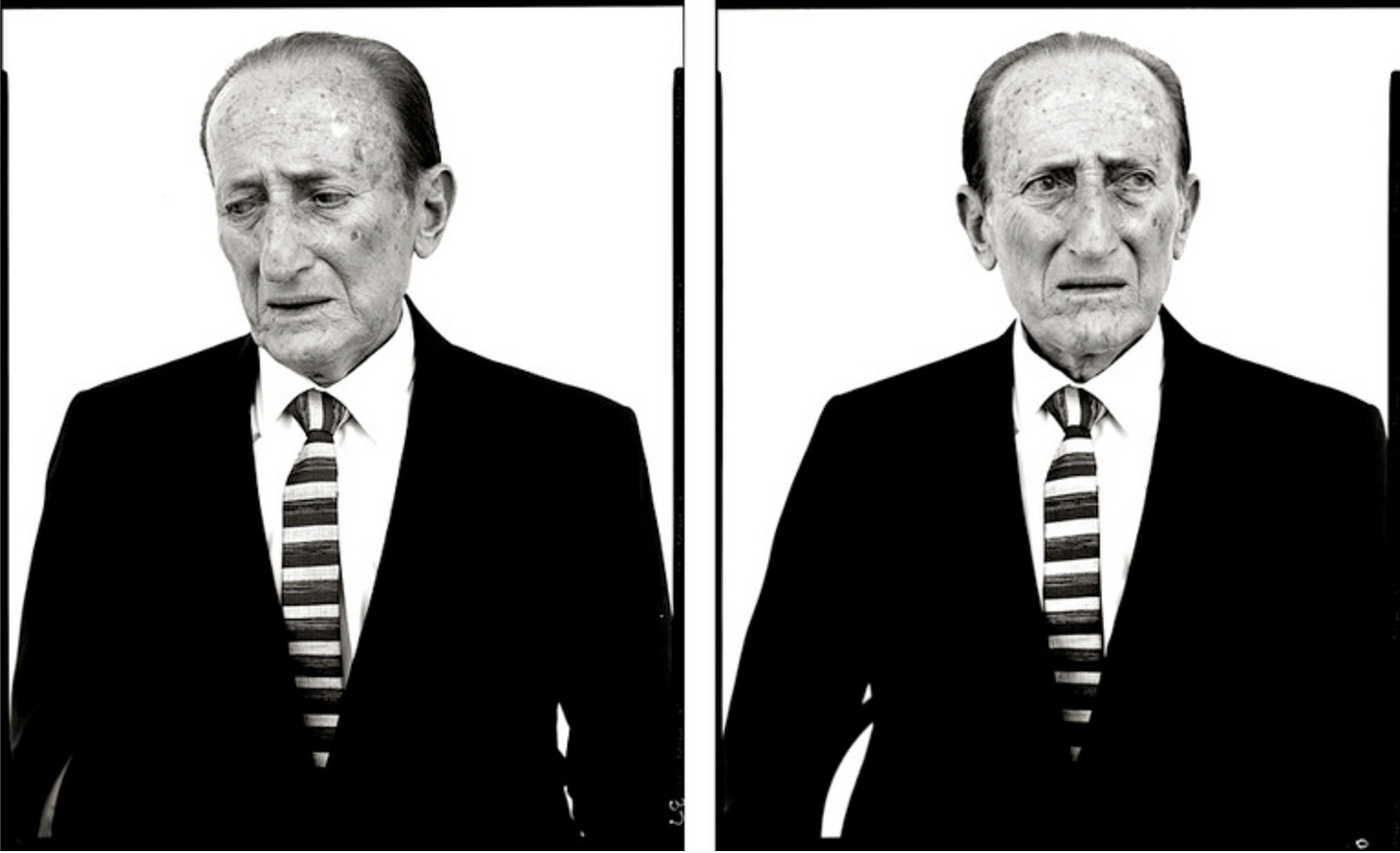

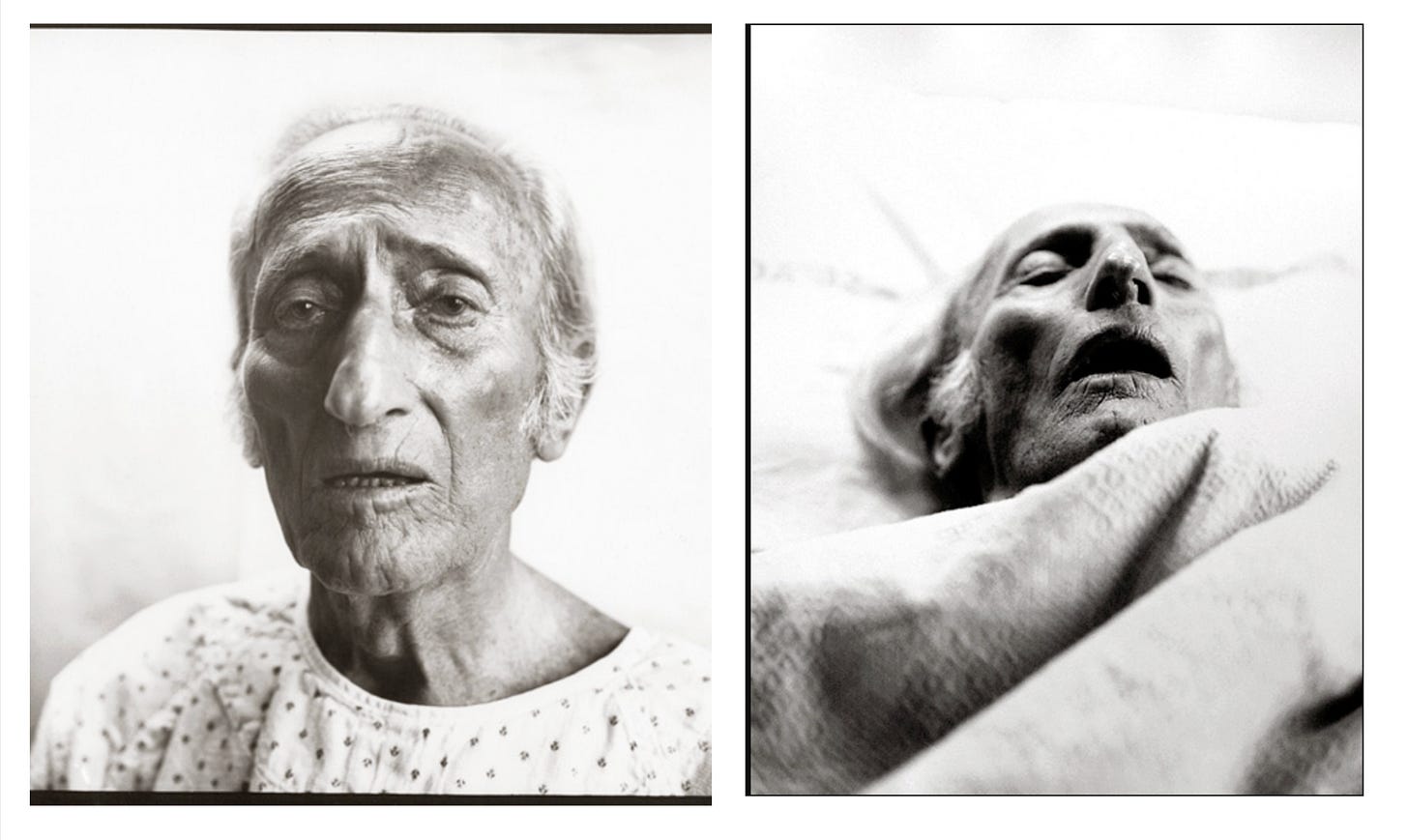

I’ve been reading a book by the cultural anthropologist, Ernest Becker from 1973 called The Denial of Death. It won a Pulitzer, and offers a take on how different cultures think about death and dying. I wanted to pair it with Richard Avedon’s photos of his father today, because he gives us an unflinching examination of the human behind our desire to perform in public photos, instagram, socials. Our desire to put a fictious veneer over our public selves.

When you pose for a photograph, it’s behind a smile that isn’t yours, Avendon wrote in his book, Immortal: Portrait of Aging 1951-2004. You are angry and hungry and alive. What I value in you is that intensity. I want to make portraits as intense as people.

Both are intense books. Becker’s relies on thinkers like Freud, Rank and Kierkegaard to do a lot of the psychoanalytic underpinning, but the idea is simple enough: We have anxiety about dying and that anxiety defines everything we do while we are alive, whether we are aware of it or not.

The natural world is terrifying and brutal, Becker reminds us. We, unlike other animals are aware of our mortality, our smallness and irrelevance in the greater world. We know we we could be eaten at any time, in a way that an elk probably doesn’t consider when she is peacefully grazing, unperturbed. And to combat this, we humans formed a biological drive to create meaning for ourselves.

Becker believes that civilization itself is a way for humans to create meaning. The humanities, the arts, sciences, technological innovation and invention, religions and faith, culture, our belief systems, the greater meaning from our occupations and careers, our beliefs about charity and philanthropy, how we enage with our neighbors, are all things we create to compensate for death anxiety. Becker believes we make our lives into hero projects, where we search for greater meaning, and in turn, give ourselves a sense of being meaningful, to stave off death anxiety and metaphorcially, death itself.

Death anxiety is so real, it has it’s own name, thanatophobia and its own wikipedia. People who are unsafe might worry about being killed through violence. Sick and disabled folks might worry about getting a terminal diagnosis, but these fears are fact-based. The fears Becker and I are talking about are the more existential ones, the ones that drive us even when we don’t think about it consciously.

Studies show that women tend to have more death anxiety than men. And children worry about it more than we realize. This can happen when a child loses a family member or hears of death in the community or online. Both of my youngest kids, Raffi (14) and Desi (10) have gone through phases of death anxiety, after their mom died. Raffi misses his mom because he was raised with her, but for Desi who was born into foster care, she doesn’t remember her mom. Her anxiety is a ghost. Will I die like my mom? she asks. I don’t want to die. Why do I have to die? I’m grateful she feels open to saying all this out loud, so we can discuss it, and be there for her.

I am a Catholic, devout at various periods in my life, although I never felt on board with the existence of heaven, hell, or an anthropormorphic God. I read the Christian mystics, went to Siena college with the Franciscan friars, was a regular at the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary convent on 96th street in NYC. Being agnostic now, I do see how saying: Your mom is in a good place, a better place, she is happy in heaven provides a happy ending to an unimaginable loss for a child, a way out of the death conversation and the anxiety of it. Faith keeps us from interrogating the finiteness of our existence. It gives us consolation. I get why faith is a comfort. I get why it is powerful.

Becker addresses this in his book. He says that as we have fallen away from religion and faith-based communities, we no longer have those comforting stories that help us make life transitions, and process hard realities and suffering. Becker couldn’t have seen this coming, in the 70’s, but science and technology are poised to be a faith replacement.

Right now, there’s a tech millionaire named Bryan Johnson who’s hero project is Don’t Die. He uses his money to atempt to game death. Johnson believes that AI will be so advanced in the future, that it will make current life expectancy irrelevant. And that new forms of existence, that might even seem unimaginable to us now, will be developed, and in this development, there will be the opportunity to not die.

Johnson believes he will not die and that he can reach immortality. And he’s not niche. He has just under 2 million subscribers on Youtube. Science and tech want to be our new religion. At least 2 million people on Youtube apparently experience death anxiety. Bryan Johnson is their leader.

Becker also talks about being a part of a group, and how we get catapulted into an Us vs. Them paradigm, which is the basis, he says, not only for, division, but also a rationale for violence against and oppression of whoever we put in the them category. I’ve written about this in the past, there are clear neuroscience and evolutionary underpinnings for this: Our brains are wired to consistently judge us vs them. Violence against folks in the them group helps us create a deeper sense of meaning. We are right and they are wrong. They are filled with hate, we are not. Punishing the thems makes our sense of rightness more concrete and viable.

When people say that our side is on the right side of history, we are combating death anxiety and creating ourselves immortal. We might not go on in our bodies, but our ideals will, our ideas will, and our fight for justice will. Being a part of history-in-the-making is a kind of immortality. We project, Becker says, our greatest fears onto “the enemy” and this becomes a way to, in extreme cases, commit genocide, war and ethnic cleansing. Our hero projects can do lasting good, but they can also create lasting evil.

Mortality can be confronting. David’s heart attack was confronting. It changed all of us. We couldn’t look away. In response to facing his own death, he has made a hundred shifts and changes to make sure it doesn’t happen again, for as long as we can put it off. And the family has pivoted to support him. He has inspired the rest of us on our own health and wellness journeys. I mean, Jesus, we are in bed at like 10pm every night, choking down protein shakes, and booking 5pm dinner reservations. LOL. I’m grateful for all the work we are doing for our health, longevity and the quality of that life, and that we have the privileges to do so. But I know all of it is spurred on by a death anxiety that I haven’t wanted to face.

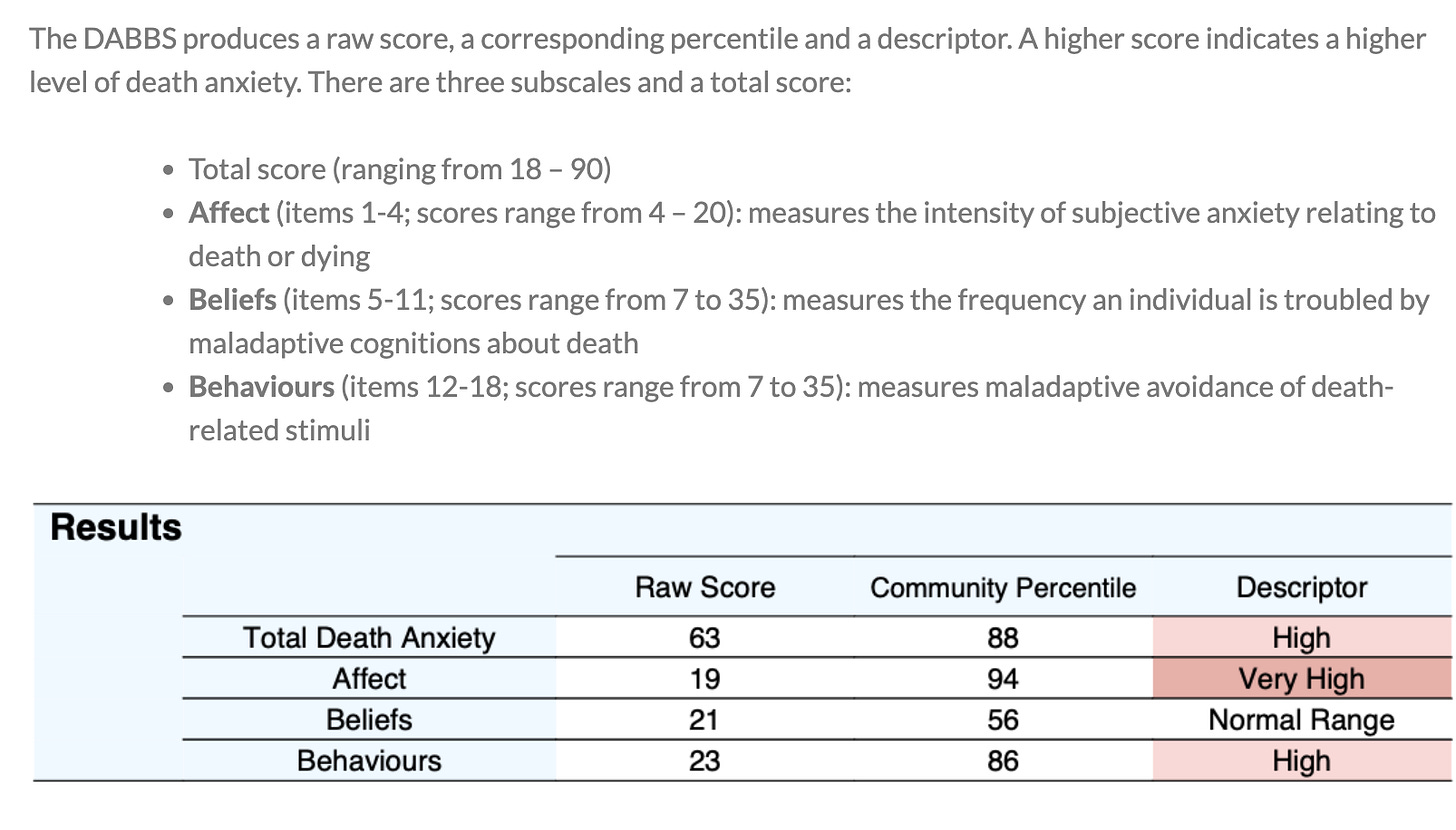

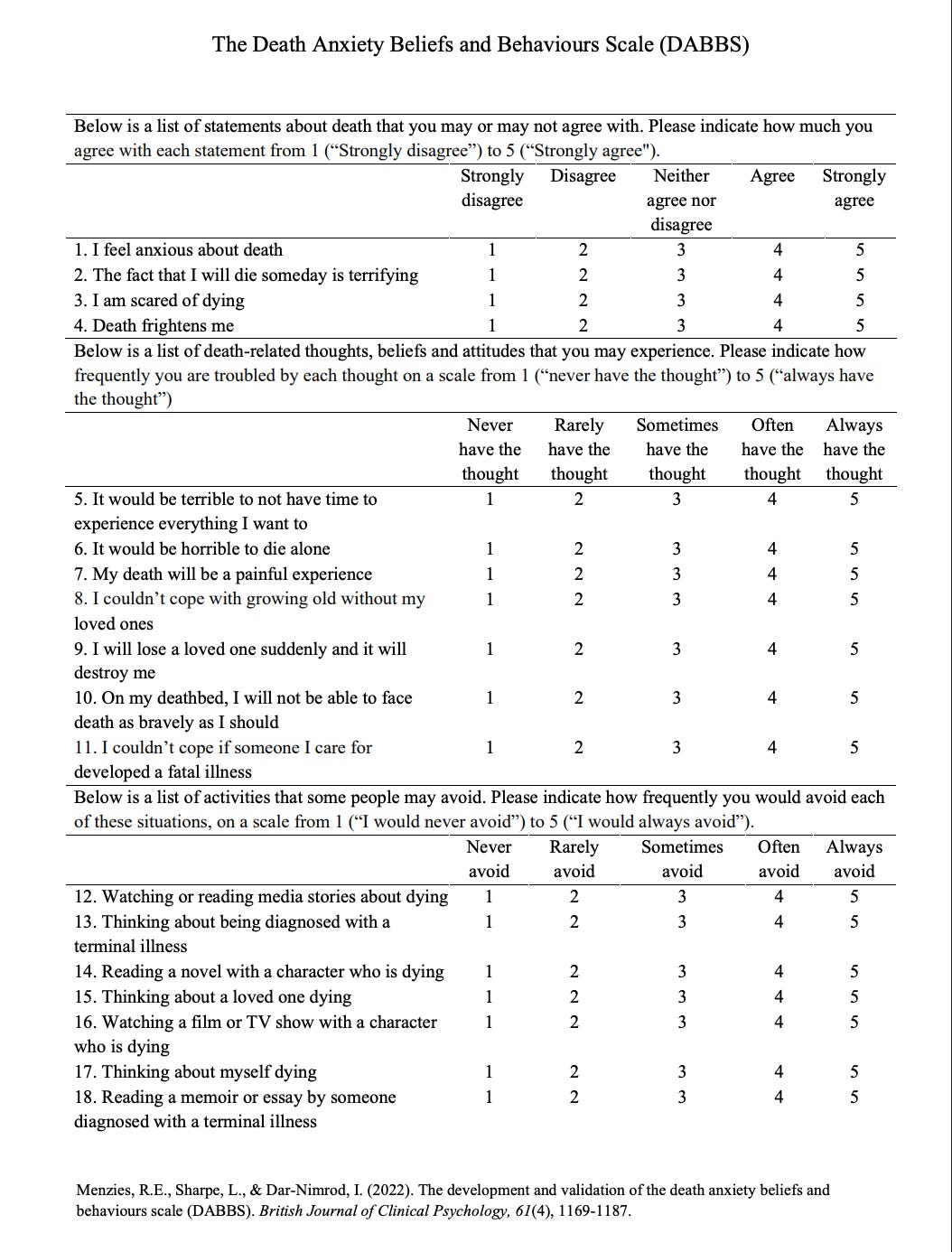

There is a test (DABBS) for death anxiety that you can take. There’s also one that uses photos to help children talk about their death anxieties (DASC). You can take it yourself. (The answer key is in the bottom End Notes section):

I wonder how health scares, close calls, accidents, terminal diagnoses, and proximity to death, play into how we feel about dying? Are we better for looking at it closely and coming to terms with it? I had to do this a bit before I had 10 hours of brain surgery. I remember being at a dinner party, right before, and sitting next to a man, also in his 30’s, who was HIV+. (In 2001, AZT and Viread had been on the market, extending lives, but HIV/AIDS was still not a “manageable condition.”) We made jokes about dying all night. It was powerful and cathartic and transgressive. It felt good to be able to laugh in the face of this big scary thing. But I was younger then. No partner, no kids, limited family. It was harder for my parents than it was for me. I could afford to leave if I had to.

Now it feels like there is so much more at stake.

What does my absence from this earth mean to me and the people around me? What will my hero project be for the last third of my life? How hard will it be to leave the people I love so dearly? How hard will it be for them to let me go? Do I care about my metaphorical immortality? Is death anxiety for pussies?

What I always come back to is my childhood fantasy that comforted me during those long, lonely, sleepless nights. That we should live the fuck out life until we get mowed down by a bus, exploded into the stars, eviscerated into cosmic dust. This is maybe the best I can offer as consolation, that it is quick and without anguish and pain.

There I go again. Always trying to push the end away. Sometimes I’m envious of elk.

_____________

END NOTES:

If you take the DABBS test, here is your answer key. Would love to hear in comments what you think of the test, what the results were and if you are surprised? And any of your thoughts about being mortal. Do you worry about death or dying? And how does anxiety about death factor into your life? Do you have a hero project?

Also…. I wrote a piece for the Guardian this week about how even the threat of hunger can change the brains of kids and impact their emotional and behavioral health going forward. I’d love for you to read it.

Even though the shutdown is near and end, families - and children, especially - continue to struggle this month. Please consider supporting families in your community!

Thank you, as always, for reading here and supporting me in all the ways you do. I appreciate you all. xo - Kim

Death ... Ooph... and wow..

This was such a thoughtful and timely read. I've faced the Grim Reaper twice. Cancer both times - the first time Ovarian in 2003 , the second time, colon in 2011. But it's been a minute since then. And since then, I have been living like there's no tomorrow in every effort to put as much distance between that time of looking over the precipice and now.

But at 68, I'm feeling that I'm losing ground, feeling the inevitable making gains on me once again. So many things are beginning to slow me down and take the 'run' out of me, including friends that are falling by the wayside with diagnosis, two of which I've heard about in the last 2 days.

A vague melancholy casts a pall over even all that is so good in life for me now. It's like, I'm always waiting for the other shoe to drop. I mean, I just can't seem to live in denial that I too will succumb to my failing flesh.

Having started writing my memoir this last year casts yet another spotlight on this truth...

Sigh.. it makes me sad, of course. I just hope I'll find a way to be graceful about passing on to whatever's next when my time comes (if there is a next) and not make it harder than it has to be. I've seen enough people resist their death and enough who didn't. I'd rather be one of the latter ones.

I'm definitely afraid of dying. Some days I can't even process how it could possibly happen to me. Other days I'm incredibly grounded in the reality of it, especially having recently lost a 39-year-old cousin to cancer. The first time I remember feeling death anxiety was after watching the film version of Charlotte's Web, when I was about 7. I remember lying in my bed sobbing. My elementary school teacher called my mom sometime after to let her know that she was worried about how much I was worrying about it. Sigh. Lately I've been deeply feeling this powerful truth-- that loss is the other side of love. Like two sides of the same coin. So grateful to have loved so powerfully, and already mourning the losses to come.