I wanted to share my University Forum Lecture with you all this week, since I think it has some solid information about what food means and doesn’t mean for a lot of people. Some of you will notice a couple little bits of overlap with the lecture I gave to Princeton high school students, but this version is longer and with more supporting research.

This lecture lasted for about 45 minutes, comes with slides (I will include some, take out anything extraneous) and if you came to the event, you might have eaten some red pozole with pork and hominy or a vegan black bean tortilla soup that I made.

Here is a friend’s bowl.

The idea was to eat together and talk about food in a new way. The room was crowded and the eaters came in droves (Bless their hearts). I hadn’t taught in a college classroom since I was an Assistant Professor in the English, and Women and Gender Studies programs at Pace University in NYC. Like eons ago. I mean I was pregnant with Lucy the last time I formally taught at Uni.

I still love talking to students. They are THE BEST, so fresh-faced and ready to tackle everything. It was fun to stretch that muscle again.

Here is the lecture. Thanks, as always for reading. xo Kim

_________________

We had only been in Vegas a couple months when my 8-year old daughter ran into the house screaming “There’s a Dead Guy in Our Backyard!”

We had moved here from NYC but not once while living there had we experienced a dead body. Cue Vegas.

David, my husband, went to investigate the body laying on the floor of our casita. Charlie, our handyman, definitely looked dead. David prodded him and he didn’t respond. So he cleared his airway, threw a blanket over him and let him sleep it off. Charlie laid there on the concrete floor for hours.

We’d left New York for Vegas and moved into an unloved 1940’s Huntridge bungalow down the road from here in downtown.

David had called the city’s Day Laborer’s Office to get some help with the house and they sent us Charlie. It was hotter than hell. 117 degrees. We had him jackhammering concrete, for Christ’s sake, so when it came time for us to eat, it felt weird to not include him.

And that is how we got to know Charlie. Over lunches.

That first lunch together, we - David, the kids and Charlie - passed plates of yakitori, jasmine rice and salad and he told us about being in the Marine Corp. He talked about his wife, Tessie, and their five kids, who were staying with family back in Texas while he and his wife tried to make a go of it here in Vegas. He talked about God a lot. About church together and the fishing they used to do with their boys.

I had to wonder why they came to Vegas at all.

He was so talented. He could lay tile, build anything, plumbing, electrical. I couldn’t figure out why he was at the Day Laborer’s office when he could be doing so much better? Why they left the kids in Texas? Something felt off during the lunch, but I couldn’t pinpoint it.

Later, long after the meal and kitchen work was done, I found Charlie slumped over in the backyard. He was crying. Sobbing, gulping for breath.

And he told us: Everything he said over lunch had been a lie. His kids, his jobs, his wife, their happy life? It was a lie. All of it. They had lost all five of their kids to child protection.

And his pool business, home and cars, everything that was dear to him. Was gone.

Charlie and his wife Tessie were full blown meth addicts.

They came to the desert to kill themselves.

We would never have known any of this had it not been for the lunches. Sometimes eating together brings a closeness and intimacy that is awkward and often uncomfortable. It slows people down.

Sometimes food gets to the real and complicated feelings people are having. Sometimes, like Charlie, you eat some yakitori together, kids clamoring to get into the conversation, elbows hitting elbows as plates are passed, and it jostles things.

Eating with us made him have to think about his own kids. For the first time in many months, he remembered what he had lost. It was painful and hard for him to come to terms with everything that happened to them and their kids.

After he started working for us, he was making quite a bit of money every week.

Enough to house them in a weekly apartment. When he was trying to stay clean, white knuckling through it, I would give him eggs from my chickens and I would teach him to make omelets with cream cheese and scallions. He would cook for Tessie in the weekly. The cooking made him feel normal. Like everyone else. He was tethered to the world.

When you are making a meal for someone you aren’t an addict, you are a part of the world and its people. The basic fundamental act of preparing a meal connected him to all the other sober, unaddicted people in the world having to do the same in their own kitchens.

But the money he got from us also fueled their addictions. The money from us made it possible for him to buy even more drugs and for them to be high more often. We were helping him by giving him work and also fueling their drug addiction.

And of course, things got out of hand….

Tessie got pregnant. While using.

I listened to Charlie’s delusions and lies when he did come to work. His plans to get married on the beach and his hope that my kids would be his barefoot flower girls and I would throw the shower for them.

It was stupid. The way his brain and thinking was disturbed and twisted by the meth. Like everything was just fine, but it was actually pure hell, he just hadn't figured it out.

He worked on our house until he couldn’t.

I cooked lunches until I couldn't.

And at some point, I decided he was a dead man walking.

I was sure he would never come back from this.

And so I wrote an essay called The Meth Lunches, which was published in a 2017 issue of Desert Companion Magazine.

I didn’t ask Charlie’s permission. I didn’t tell him I was writing about him. I didn’t worry what he might think because - if I’m being honest - I didn’t see him as…human.

He occupied a special part of the tweaking universe that is no longer a part of our species.

To me, Charlie was a ghost. I gave up on him.

Turns out, I’m the asshole. Because this is Charlie and Tessie today.

This week they are taking their youngest daughter Hayden, who is 7 and absolutely perfect, to soccer practice. They bought a house in Texas. Charlie is working as a contractor. They see their older boys, now nearing adulthood, for creek fishing. They are making amends. They stand in the school pick up lines and yammer with the other parents and eat dinner together and love Jesus. Tessie is, after dropping out of high school, enrolling in college.

What Charlie and Tessie accomplished was extraordinary.

The statistics for getting off meth are devastating. Studies have shown that the average recovery rate for people enduring meth addiction is around 37%.

So when I got the chance to write a book based on the essay, I called Charlie. I wanted to do this right this time. I had counted him out.

How many other people had I counted out?

How many people have I rendered invisible?

Who have I counted out?

I wanted to apologize for counting him out. I found him sitting at his kitchen table, on Facetime with Hayden playing Barbies on the floor. He asked me for my fried rice recipe and I sent it. And then he sends me a photo of what he made and it looked…. perfect. The most beautiful fried rice I’ve ever seen really.

It was a relief. A full circle moment.

Cooking feels like health to Charlie. Saneness. Normalcy. A boring chore that ultimately binds us to all the other people doing this boring chore at 5pm. Charlie even cooked in the rehab that helped get him sober. The program required the men in recovery to cook meals for the unhoused.

Charlie told me he put a lot of effort into making breakfast for this clientele because he said they would throw bagels at him if it wasn’t any good. It was a lesson in humility and service.

Where addiction and homelessness really remove people from the patterns and rituals and connections of life and humanity, cooking can be a way to bind us to it.

And this is probably why we have so many food cliches in our lexicon. They are all over our feeds.

“Food brings us together.”

“Food is love.”

“Food connects us.”

Perfectly crafted images. There is plenty and abundance. Perfection. The food itself is intentional. Hyper-curated. Privileged. Everyone who eats the food is happy, smiling, laughing. They have amazing lives, it seems. Their food, their choices all signal that. It is a monoculture of food happiness. There is ampleness and beauty.

It’s also a lie.

I shop often enough at Smith’s Supermarket on the corner of Maryland and Sahara. My hairdresser calls it “Murder Smith’s.”

I was there one day with my daughter, Edie. Checking out. The cashier was Johnnie, but everyone calls her Moose.

She was checking out my food, running it along the belt. Edie was bagging. We were chatting. One of life’s great joys is embarrassing my children by being super chatty with the checkout folks.

A line formed behind me. And in the middle of the conversation, without so much as a hiccup in the checking out of my groceries, Johnnie told me that she had been locked in a closet in her childhood home and starved as a child.

This, weirdly, formed the basis of our friendship. We had coffee. She talked and I listened. I wrote it down.

She wanted people to know what happened to her. Her story.

Now, we know that food can be used as a weapon. It’s been happening since the beginning of our existence

And it makes sense: we are dependent on food to live and so it makes the perfect weapon. And historically this has happened a lot. In the last decade, we have seen it happen in Sudan, in Yemen, in Ukraine. And we are seeing it happen in real time in Gaza. But it doesn’t just happen in a theater of war.

For example, food is used as a weapon in incarceration. Everyday.

Inmates who are not compliant can be controlled by food. They can be given a meatloaf like concoction for meals, made by mashing together other leftover prison meals, meat, potatoes, margarine, syrup, vegetables, eggs until it’s formed into a meat paste and heated through again. The existence of Nutraloaf has been the source of many litigations and more than a few supreme court rulings. It is ubiquitous in the criminal justice system. The idea is compliance and behavior modification by food.

When Johnnie was a child, her single mother devolved into psychosis, delusion and untreated schizophrenia. Johnnie was the youngest and when her sisters escaped the house, she bore all of her mother’s delusions and punishments.

She locked Johnnie in a closet. She cut off her food. She beat her wherever she had the chance. She killed the household kittens, so Johnnie had to sneak out of the closet and bury them in the backyard by herself.

Johnnie told me about sharing Milk Bones with her dog inside the closet. She would feel for the halfway mark in the dark, splitting the biscuit in two. She always gave her dog the biggest half. This was critical for her. She explained how she protected her dog over herself and why that mattered to her.

“I would starve for her,” she told me.

This goes against everything we all want to believe about food. That food is love. That cooking is about abundance and comfort and providing love. That it brings people together.

“The Table” is such an iconic image in food culture. Food in context of the table is about being a conduit for beautiful things happening. That food should look beautiful. And be home made. It should be perfectly plated. Sourced from farmers who never exploit workers, making it more expensive and elusive to regular people and more punishing for workers. We should know the provenance of our food and judge it’s worth that way. That it deserves to be photographed and posted for people to ogle and long for and be jealous of and wish they were there with us as we consume it.

But we rarely talk about what the lack of food means for real people.

Humans are changed irrevocably by hunger. And not just for the one person who is hungry. All of us experience the residuals of hunger in our communities.

Here’s an example of that:

This is straight out of the neurobiology playbook (to read more about this: Dr. Robert Sapolsky’s Why Zebras Don't Get Ulcers: The Acclaimed Guide to Stress, Stress-Related Diseases, and Coping

Let’s say that a woman is pregnant. She is poor, possibly has other kids to feed, and is scrimping to save money. She isn’t eating well or enough. The fetus learns about how plentiful food is in the outside world.

It’s not.

The fetus learns that if there isn’t a lot of food in their world, they should save up. And something happens to the fetus which is PERMANENT.

It’s metabolism gets “thrifty”

For the rest of this child’s life, they will get very good at storing food. That means their bodies will hold onto calories. These folks will end up with a greater chance of developing life ending and life altering diseases, like adult onset diabetes, hypertension, heart disease and obesity that is resistant to healthy diet and exercise.

And the research tells us this continues not just for this particular baby with the mom who was hungry, but also for her baby when she grows up. Remember she permanently has a thrifty metabolism, so when she gets pregnant, her body will do what it’s good at - it will steal nutrients from her fetus, which will give that fetus a thrifty metabolism and so on and so on across generations.

We know from two very particular studies that how we manage childhood hunger and give kids in families resources and extra cash they always do better.

Take The New Hope Project, a program in Milwaukee, which tracked working families just over the poverty line.

They found that roughly $3,000 per child, per year for the first five years of the child’s life was community-changing. That $15,000 investment in families produced adults who worked 135 more hours a year in their 20’s and 30’s.

In the Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences Journal in 2022, researchers found that giving families extra money for their children didn't just change the family, it changed the actual brains of children.

More money for young families = increased brain development for kids.

We also know that attaching extra cash to every child has an outsized impact on co-morbidities that we rarely think about, like giving more women the opportunity to keep their babies instead of giving them up for adoption. Or helping poor families get off the radar of Child Protection making family separation more unnecessary. We also could see more women able to leave relationships when domestic violence is present.

Extra cash for families would have massive implications for all of us because the more stable the family is, the more stable the children, the better they do in school, the less crime and delinquency, the more stable the community, the more productive hours in the workforce for future generations.

The answer to many of our communities problems is simply to invest cash in young families.

Okay, so I want to pull apart this idea that food is love.

We all say it. Pizza is love. Pasta is love. Carbs are love. But it’s not entirely true. And Johnnie’s childhood underscores this:

Food is not love. Feeding people is.

When a baby cries out and a parent or guardian comes to them with a bottle or breast, or a comforting snuggle, an attachment bond is formed.

The baby is hungry. The caretaker responds with food. The baby learns that they are safe. Their needs will be met. The world is kind and reinforcing.

When food is not available, either because the family is in crisis - like with mental illness and addiction, foster care, forced family separation, or abuse and neglect - or because there are comorbidities of poverty, like having to work multiple jobs, find formula, bring in caregivers who might not be experienced, the baby learns that she is not being cared for, that the world is harsh and unsupporting. That there is danger.

The absence of food is the lack of comfort and security.

Food shows us what our world is like.

For those babies who were fed regularly, attached to caregivers, they grow up to have relationships that reflect that connection: These babies turn into adults who can have healthy, boundaried relationships with the people they meet. They are able to seek out support and comfort from other people. They can manage their emotions and handle conflict.

But babies who were not fed regularly or adequately, often end up having relationships that reflect those schisms. They might crave closeness but struggle with that closeness when it presents itself. Their relationships can feel terrifying because any kind of feelings of dependence and vulnerability set off warning bells that something isn’t right.

They might prefer casual relationships to committed ones. They can be prone to withdrawing from people in close relationships because the feeling of vulnerability can be unmanageable.

In extreme cases, as in children who have been neglected and improperly fed in orphanages, for example, the kids can grow into adults who find the love and compassion given to them acutely painful and will do whatever they need to do to ensure they are not loved. This means using antisocial behaviors that disrupt families and relationships to ensure they remain uncared for. Lying, stealing and aggression are common enough strategies that kids from extreme depravation use to crack apart their relationships.

These feelings can be healed in some ways but not cured. They are lifelong.

As an example, Johnnie wanted to be a part of my book launch. She wanted to come to this lecture. We worked on setting her up for success for a year. My daughter, Lucy, was going to pick her up, and Drew was going to meet her, and her friend from Smith’s was going to come with her.

She always wants to make it, but she can’t always make it happen. She wants and desires the connection. But when the connection comes, it’s too much. Overwhelming. Terrifying. And so the thing she wants and needs and craves is ever elusive. When it comes to close, it hurts.

That is the quagmire of attachment disorder. It is also Johnnie’s quagmire.

Johnnie learned how to pry the bottom of the closet door open enough to run out, grab a bag of sugar from the counter - C+H sugar, a brand she still buys today (more proof that brand preference gets set at a very early age and it doesn’t always have to be positive) and tip the bag into her mouth and then run back before her mother noticed.

To this day, Johnnie works in a supermarket. On purpose. So she will be surrounded by food.

Think about that: How her trauma defines her life. What job she took. Her rituals. How she copes. Johnnie has engineered her life so that she will never be without food.

And yet, her relationship to food is messed up still. Even now in her 60s, Johnnie eats because she has to stay alive, not because she enjoys food.

Eating is a stressor. Something she has to do, as if her stomach is an annoying alarm clock she has to listen to and respond to.

She wonders aloud if she deserves to have food at all. If she deserves to be loved and nurtured. Because feeling safe and loved in the world is directly connected to food.

I didn’t mean to run a food pantry.

It snowballed from a few rolls of toilet paper in our little free library, during the early days of the pandemic, to a full-on7-day-a-week operation with a front-yard refrigerator, dry pantry, and extra fridges and freezers to hold overstock.

We started a facebook group for the community. We announced all new veg and meat deliveries with videos posted in our group. Local news turned up. This brought the valley to our front yard.

Up to 10 cars could be queued up at any time. We partnered with a non-profit in Henderson to get the run-off from supermarkets, the almost expired meat, veg and dairy that they were clearing from shelves. We put all the food out for the community as if it were a green market.

Neighbors donated. Often. And when people finally got government checks, neighbors who didn’t need them, Zelled and paypal-ed the money to us. This was a total community effort.

For many families, we were able to directly buy things they requested, give them funds to purchase groceries themselves and hand out gift cards at Christmas time.

We even helped a few folks find places to live and kept a few from being evicted because corporate landlords were evicting tenants, while taking federal funds, even though there was a moratorium in place.

UNLV students formed groups collecting leftover foods from retail chains, like Starbucks and local businesses like Juice Stars. So we had branded, ready-made sandwiches and beverages ready for people all the time.

Our cookbook group out of the Writer’s Block, Please Send Noodles pitched in with two initiatives designed to get better food choices out to people.

One: 100 Dinners, had us cooking 250-300 meals once a month for car pickup. We didn’t do this alone - Main Street Provisions - The amazing and generous Kim Owens is here tonight - showed up with box after box of restaurant-quality meals to add to our stocks, and oversaw our efforts to make sure all the food was cooked and handled safely.

Two: We responded to the lack of choice people had around the food they were eating.

What we really wanted to offer people was: choice. We noticed that there wasn’t a lot of choice over food for people. This is a problem for lots of families all the time and not just during the pandemic.

A lot of families were able to pick up food boxes handed out by the government. But they were often the same foods, every time. Precooked meatballs, sour cream, cooked taco meat, a bag of tortillas, a bag of beans, a proliferation of canned vegetables that included weirdly insane amounts of chickpeas.

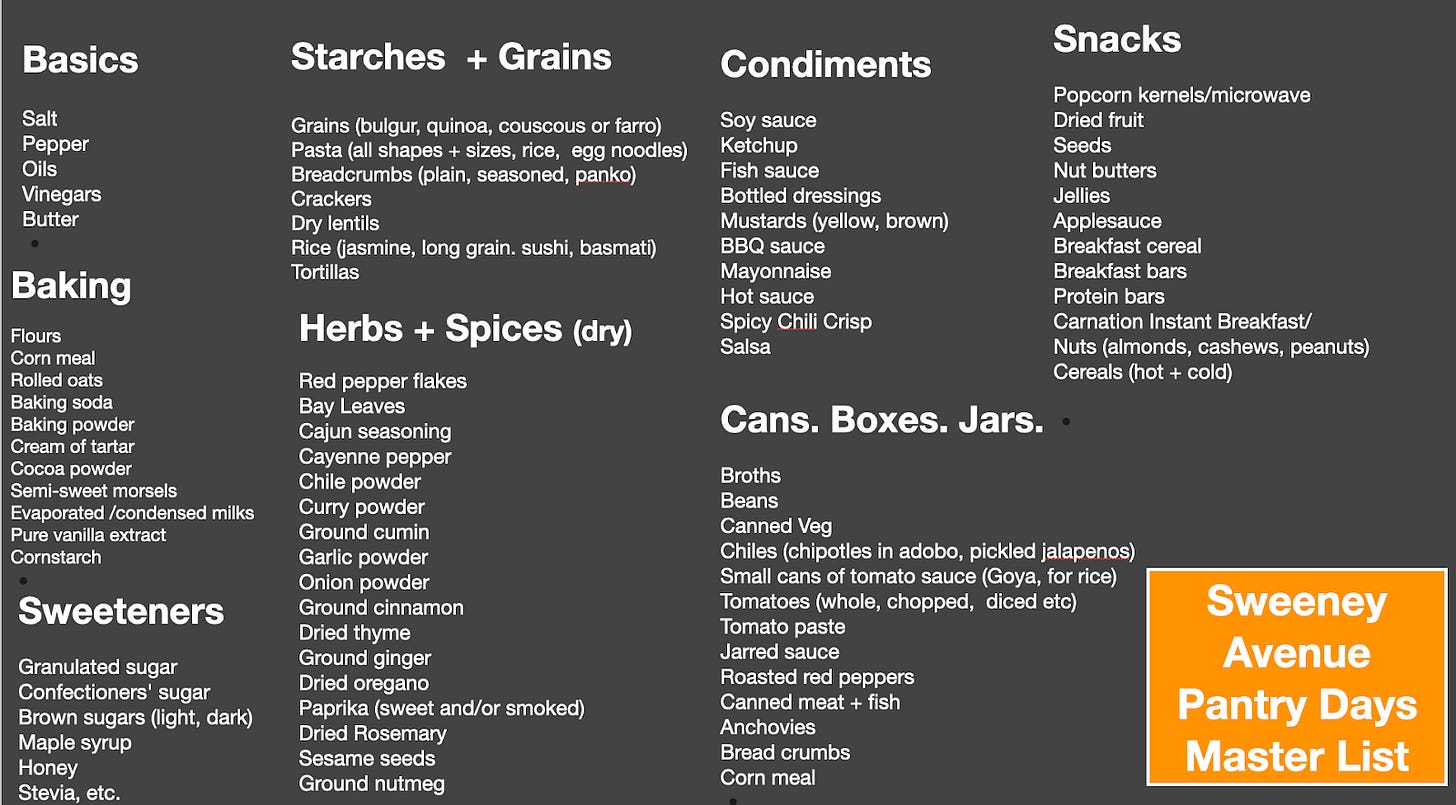

So Please Send Noodles came up with the idea of offering Pantry Days as well. Every other month, when people had used most of their checks, we’d do a community drive for pantry staples. Here is an example of the list that went out to the community.

Our pantry days were meant to fill in the holes with culturally appropriate and desired ingredients. Pantry supplies that people can use to cook more creatively with what they get in their Farm to Family Boxes.

This has become something that I am very sensitive to now - how many people in our communities do not get to choose the food they are eating.

That it is handed to them in boxes and this is what they get. Period.

Here’s what I learned from running a pantry:

Charity is about immediate needs. Justice is about social change.

And this got me researching and reading. I felt something was off. Something wasn’t working. A lot of what I thought, I couldn’t even express or assemble into language. I have to thank Andy Fisher for his book, Big Hunger: The Unholy Alliance between Corporate America and Anti-Hunger Groups for really helping me put my feelings into words here.

Anti-hunger groups are not always in it for the right reasons.

It did not go unnoticed that ultimately our small pantry was shut down, not by neighbors or community members, but by a nearby pantry, who felt that we were encroaching on their good work. There is no anti-hunger major in college and no official canon of study, so lots of people who are doing this work, don’t have the experience to understand the greater systemic issues at play.

These are regular folks interacting with people in crisis in churches, community centers, schools and they have limited experience. There is no anti-hunger curriculum or college degree. Mistakes, bad ones, are going to happen.

Food Banks are in bed with Big Food.

Big Food companies are “donating” millions of dollars to food banks and hunger orgs. And putting their executives on the boards of food banks.

This does a couple things:

It gives these companies the halo effect of caring about hunger.

And it gets them the privilege of sending foods to food banks that they cannot sell, thus eliminating their waste and overstock problems. Food banks often struggle to say ‘No’ because food is food and they need quantity to fill those warehouses and feed people.

Feeding America, for example, which supplies foods to Three Square here in Nevada, is funded by ConAgra, Walmart, Costco, Amazon, Cargill, Target, Trader Joes, General Mills, Kroger, Tyson, the list goes on.

Some of these folk sit on their boards. And when food bank boards are full of Big Food representatives we know they are advocating for putting their products into food banks so that it can set the taste preferences of the poor across generations. Even Johnnie, who had terrible associations with food still uses her mother’s brand of sugar. This should tell us how potent this marketing is.

The food bank system is a holdover from Reaganomics + shouldn't still be around.

In the 80’s, Reagan cut lots of benefit programs for the poor. Food banks and pantries went from emergency-related and temporary to powerful, fully-funded pipelines. Food banks invest in more and more permanency: bigger super-warehouses, trucking and delivery systems, highly paid management, etc. They are making themselves more and more entrenched as a solution when the solution is ending poverty, not feeding people. And this leads me to the big one….

We need to shift the focus from hunger to poverty.

This is the Feeding America home page.

Feeding America is the largest U.S. charity by revenue. Proving that everyone loves to feed children. Republicans love supporting food businesses and Dems love charity.

The food bank system likes to tackle hunger. Particularly kids hunger which we all agree is unacceptable. How can anyone argue with ending child hunger?

But they stay away from poverty, which is complex and rooted in things that aren’t easily fixed.

Hunger is a problem. But it’s a by-product of a much larger systemic issue and that is poverty.

Poverty is harder and more complex to fix. We like to do these easy fixes a lot when it comes to poverty, and food banks often send us messages that we are doing our bit to eradicate hunger by finding some old cans of peas in the back of the pantry and donating them.

Fought hunger today. Check.

I’m reminded of Kenneth Kolb’s disrupting book Retail Inequality: Reframing the Food Desert Debate which challenges the very idea of the term“food desert.”

The term was coined in the 90’s to explain communities with entrenched poverty, blight and little access to a supermarket. Black activists in those communities asked for access to healthier foods for the community, and researchers - who were largely from middle and upper income brackets and many of whom were white - believed that meant better access to a proper grocery store.

So we went into these depleted areas and created all kinds of interventions to help bring in supermarkets.

But this missed the point. In small city after small city, grocery stores in food deserts went belly up. Why? Researchers followed up and found that “more than half of food desert residents bypassed their closest grocery stores and chose their preferred grocery store miles away.”

We wanted it to be as simple as putting a grocery store with a beautiful wall of vegetables in a blighted area and everything would change.

But it didn’t. Because how people eat is intersectional with how they live, and that makes everything we eat, consume, purchase a political statement.

Lastly, I want to introduce you to Ms. B.

Ms. B was a pantry regular. She is an unhoused Korean-American woman who often came to the pantry for supplies with her chihuahua, Princess.

I still visit her at Jaycee park. And she calls me every couple of weeks to tell me what’s happening. She is pretty mentally ill. Lots of hallucinations and delusions and shadowed men coming to hurt her. It is always hard to follow along and to suss out what she is trying to say.

But then, there are these moments of clarity.

There are all the times she showed up at our 100 Dinner cooks and dove in, helping us. She boxed up food, washed dishes, stirred pots of stew, talked to everyone. She didn’t just receive, she gave.

People, even in the depths of poverty do not want to just be given to. They want to give as well.

We saw this time and time again at the pantry. People came to take, for themselves. They'd ask: Hey! Can I take a box for my shut-in neighbor? Can I take this roast for my friend, she has four kids and isn’t doing so well?

People deeply desire equity.

Unlike Becca, who saw herself as an outsider, Ms. B wants to be part of our bigger community. And when we let her, she is an excellent contributor.

One day, Ms. B came to our house. It was mid-summer, strangling heat. I had known her for a while then. I opened the door to find her, broken, a horde of buzzing flies circling around her. She was holding a bulging towel. (PAUSE) I knew who was inside.

Princess had died and Ms. B didn’t know what to do with her best friend’s body.

It is a gift to be the person who comes to you holding their dead best friend in their arms, asking what they should do.

And this is really the most important work of small community food organizations - it isn't exactly about food at all. These small organizations can carry the emotional weight of the community. The food gets us in the door, but the point is to sit, stay awhile, connect, listen, create connections when there aren’t any. To never turn away, even when it is complicated and hard to keep going.

A part of Princess’ ashes are buried under one of the trees in our front yard so she can come anytime to visit her. (If we sell the house, I might have to put a clause in the purchase agreement)

Sometime during the pandemic, I went with Ms. B to check out her van. It was parked in a lot. It didn’t drive.

The van was stacked with all kinds of things, floor to ceiling. Pillows, blankets, clothes, lamps, things she might need in the future. It was too full for her to actually live inside. It was more like a closet.

In the front seat of this non-functioning van, parked in a parking lot in a nearby church food pantry, she had a pot filled with scallions. In the drivers seat.

It was truly the most surprising and life-affirming thing I had seen amid so much bleakness.

The scallions roused her memory. Ms. B talked of Korea. Of making kimchi in her village with the other women. This is known as gimjang. She was thrilled to get daikon from me when I had them in stock at the pantry. She said she wanted to pickle them, so I also gave her bottles of water, rice vinegar and a little baggie with sugar.

But why would an unhoused woman who lives in a park need scallions? And daikon? Why would she be making pickles and growing a pot of sprawling scallions in her van?

Because it connects her to Korea. To who she is. To her memories. Food really does this best, I think. It brings us right back to places and people that are who we are at our core.

The food connects her to the land and the dark soil that she crumbles in her fingers, which she tells me is better in Korea than here in the desert - no surprise. And she talks about the cabbages, radish, persimmons, peppers and onions they grew on their farm.

And in a moment of pause, she tells me about her father and their farm. In Korea then, women were not allowed to inherit property, so her father adopted her male cousin and the farm passed to him. She remembers what a loss this was for her personally. She so loved the fields and the traditions of harvesting, processing and preserving foods from the farm, and the cooking that came along with that.

Losing the farm changed everything. It changed the course of her life.

Her new life’s dream became freedom.

What Ms. B wanted most was to live her own life, on her own terms, in the United States.

And after she said that, she smiled. Looked at the scallions growing in the sun through the windshield, and told me how lucky she was to be living her dream.

Thank you so much for having me.

This is the most thought provoking article I’ve read in a long time

Thank you for all of this.