Safety.

When do we feel It? Who deserves it? And who is a threat to us having it?

There is a specific scene in Silence of the Lambs that I made my older daughter’s, Lucy and Edie, watch when they approached teenager-hood.

The scene takes place in a deserted parking lot, at night. A man, Jame Gumb, who turns out to be serial butcher, Buffalo Bill, is wearing a (fake) cast on his arm. He is struggling to wedge an unwieldy couch into a van. He drops it, cusses, gets frustrated. A young woman, Catherine Martin, is walking home with groceries. She is nearly home. She feels safe. She is in her own parking lot. This is her space. But it’s not an accident he is there. We, the audience, know better. We saw him there with his weird-ass night vision goggles scoping her out her. Waiting for the right time.

We know what’s going to happen. Catherine doesn’t. The couch ruckus makes Catherine stop. She sees he is struggling, and quickly assesses her surroundings. She sets down her groceries and grabs one end of the couch. He grabs the other. They struggle with it, but manuevers it, so she has to back her end into the belly of the van and he pushes from his end. Finally, the couch is in.

Catherine is in, too. Trapped. She never makes it home.

There are a couple of important moments here: The moment Catherine surveys her surroundings and makes the decision to help Jame, and the split second she allows him to turn the couch around, so she has to back into the van, pinning herself inside and making herself vulnerable.

In each split second, she has to make decisions about her safety. I always wondered in every little minute of her decision-making what her gut was telling her.

This is where an instinctive reaction, known colloquially as a gut feeling, takes over. A sudden sense that something is wrong or right about a person, situation, or choice. There is no logical brain here, it’s strictly feeling. It is, I’ve found, one of the best forms of self-defense. To simply be aware of what you feel. I wanted to teach my girls to listen to and believe their intuition.

These intuitive choices, of course, set into motion other consequences I hadn’t yet considered: What does it mean if your gut keeps you from helping someone else? Or you prioritize your sense of safety over other people’s needs or safety? Or what if your sense of safety is not accurate and you are hypersensitive about things that aren’t dangerous? What if you are told things are dangerous that aren’t by family, friends, churches, governments, culture or media? What if what you are afraid of is not dangerous to you at all, but you believe it anyway, what happens then? What if, your safety comes at the expense of others?

This played out, in real time, during COVID. Many of us felt that safety meant staying home, pulling kids from school, socializing only in small groups with tracked exposures, taking the vaccine and wearing masks. Other people felt that school shut downs, masking mandates and vaccine requirements were inappropriate asks, that these “safety measures” might not make us safer, might be more dangerous, and represented government overeach that compromised people’s civil rights.

These folks felt safety was used as a weapon.

The example of Jame and Catherine is fairly clear cut. One is a clear predator and one is a clear victim. We, as the audience, have access to his dark intentions. Simple. But change Jame’s race to Black and keep Catherine white, and a whole bunch of new information gets factored in. Like the lynching of Black men during Jim Crow for speaking to or engaging with white women in everyday life. Some 25% of all lynchings - which were meant to create terror to keep Black people compliant, submissive and in line - were false accusations of Black men interacting with white women. This includes, whistling at them, talking to them, or looking at them.

This is partly why the name Karen and the act of being a Karen became part of the lexicon.

White women are absolutely imperiled by the aggression of men, we also benefit from proximity to white male power and often leverage it. Our exaggerated or strongly held fears for our own safety can create peril for Black men, who are often perceived as dangerous by walking around in the world.

In 2025, a white woman accused her Black neighbor of “making her feel unsafe” by simply parking his car in his own driveway. When she was told he lived there, she said: '“I don’t believe it.” In 2024, a Black man was accused of attempting to rape and kidnap a white woman in a parking lot, only to be exonerated after it was proven she made it up. In 2022, a white woman accused a Black man of robbing a home. Turns out he lived there. In 2000, a Black man birdwatching in Central Park was reported for “threatening the life” of a white woman, and “attemped to assault her” when video evidence revealed otherwise. He now has a birdwatching TV show on National Geographic.

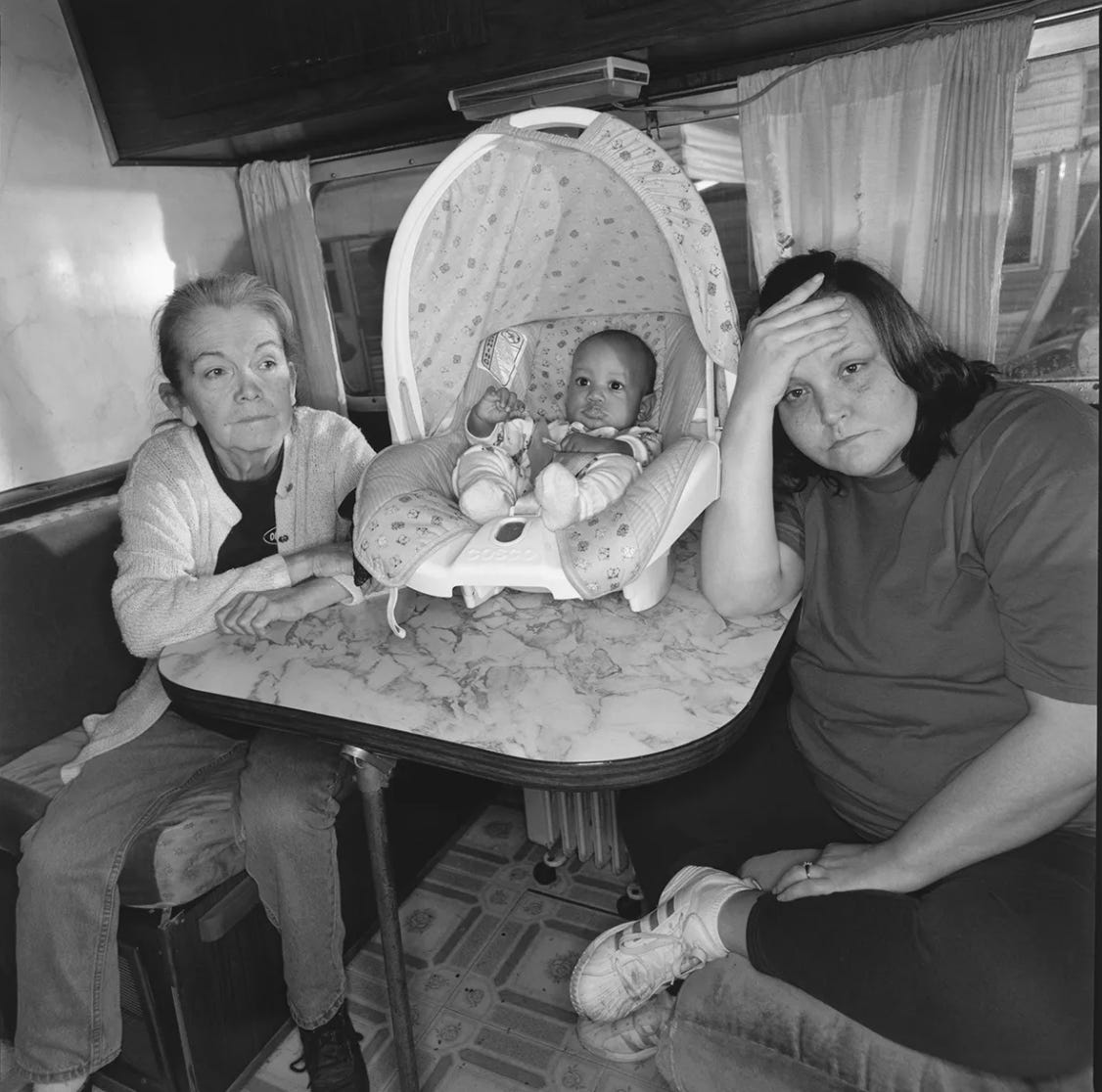

The biggest education about safety came for me as a foster parent. To do the job correctly, it meant caring for the family and not just the child. And that family can sometimes be highly imperfect, and their problems intimidating, even scary. Foster parents, trapped in middle class bubbles, often don’t feel safe around the co-morbidities of poverty. People’s lives can feel so foreign as to be a danger.

One of the sibling groups we took in had a mom who really struggled with mental illness and poor mood regulation. The poverty they experienced made her medication regime scattered and not effective.

“I never talk to mom,” the previous foster mom told me, referring to the children’s mother, as a way to prepare me for visitations. “I’m afraid of her. She yells at people, she’s out of control. I stay in the foster parent room whenever we have visits.”

This mom violated foster mom’s sense of safety. Foster mom was a middle-class, Christian woman whose husband worked at a mega-church and she was a stay-at-home mom. Her world was small, delightful, stable and protected. Everything was neat and ordered. Having lunch with a person who raged and held bizarre opinions was not on her dance card.

One of the things that happens in foster care is that the system is set up so that foster parents are considered the good parents, while biological parents have to be bad. Jame and Catherine. These dichotomies make us feel safe. We play roles.

Weirdly, when I met mom, something about her high-volume anger, reminded me of my own mother. Someone who was hurt and hid all that vulnerability and pain underneath the rage. I used the same stealth techniques to melt this mom, as I did to melt my mom’s unruliness. I figured, from experience, this mom was mush underneath all the bravado.

It took a lot of time, but she started talking. I listened. I kept calm when she ranted. I got frustrated sometimes. She made the same mistakes over and over, digging into unhealthy practices, two steps forward, four steps back. She dated men who beat her and then lied to police so she would go to jail, not them. Left jobs she needed to keep. Screamed at people who could’ve helped her. Hustled men for rent money. Got fucked up by the men she hustled for money. She could never quite right herself. Or stay in an apartment or keep a cell phone or even make most of the visitations with her kids. Even as she failed her kids she loved them. And they loved her.

But she was never dangerous and I was never unsafe.

Foster mom would never have been in any danger either. Her desire to sequester herself out of fear was exaggerated, and yet, it’s her right to set those guidelines for herself, to listen to her own gut, to decide for herself what she could and couldn’t handle. But by hiding herself away, she disconnected herself from a mother who needed support, and who wanted to be connected to her children, by text messages, updates and photos.

We make choices. One person’s safety is another person’s danger.

One of the questions I used to get often at readings and events around The Meth Lunches was how I let our kids interact with people who came to our food pantry during the pandemic. My son, who was then 10, was close to Becca, a Mexican trans woman, perpetually unhoused and in active meth addiction. She came by daily for supplies, to borrow David’s bike tools. I was always around the kids, but I also listened to my gut. I sensed that Becca wouldn’t hurt him. They worked on their bikes in the driveway. Upside down, wheels in the air, exchanging tools and tinkering with chains and derailers. Raffi used to run in and get special snacks to share with Becca.

One night, Becca was doused with gasoline and set on fire by her street boyfriend. She came to our door, charred and broken. She got out with the clothes she wore. I had never seen her in so much despair. Raffi made her a sandwich, a soda and some cookies. He sat with her while she cried about her terrible life, and then made a bed for her in the back of our Jeep. She stayed for a couple nights.

Safety by proximity. A little less for us, a little more for Becca.

Our undertsanding of what it means to be safe matters now, because safety is being used by our government, as a weapon. Our government is telling people they aren’t safe.

There is Tren de Aragua, the Venezuelan gang that has dabbled in sex trafficking, stealing money from ATMs using malware, and extorting and kidnapping people. In early 2025, Attorney General, Pam Bondi, said that this group was a“foreign arm of the Venezuelan government” that has “invaded our country.” Trump himself said that TdA had “invaded and conquered” cities.

How many of us have been terrorized by gang members last year?

The year before?

In 2024, the government knew of just 100 confirmed TdA members in the country. But the Trump administration in 2025 claims to had arrested 2,600 people with “afilliations” to the gang. The goal of “eradicating terrorist groups” is to engage our sense of safety. To make us afraid, so we will distrust immigrants and Venezuelans.

There is no difference between worrying about TdA and worrying that Haitians will eat our cats in Springfield, Ohio. Or that Somali immigrants in Minnesota, who Trump says comes from “barely a country,” will steal our money with fake daycares, because they are “garbage.” If we blame Somalis then we won’t blame billionaires and oligarchs, and corrupt presidents and politicians, for their indifference to our suffering, to our senses of safety. If we blame Mexican and immigrant workers for taking American jobs, we are blaming the wrong people. We are engaged in the pursuit of a safety that doesn’t exist.

We are told we have to “secure the border” and “restore the rule of law” and this means we need federal officers in our cities, hurling poison gas, grabbing families out of their homes and vehicles, tazing protestors, shooting them dead, even as they try to convince us they are “domestic terrorists” who deserved to be killed for just being there. We are supposed to feel safer, but it also feels the opposite of safe, and every video out of Minneapolis, has proven that.

Politicians want “harsher penalties” and “more armed police” to tamp down crime, but we know that crime is solved by better education, better family support, better commmunity-minded programs, government entitlements, more housing options, better work opportunities, comprehensive and afforable health care. The death penalty and masked agents disappearing people, doesn’t make anyone safer, or steer people away from committing crime.

Fear is a powerful motivator.

It is purposeful. It keeps our brains in fight or flight. It is paralyzing. That we stay in the foster parent room, sequestered away, while we listen to our gut. When they send in federal agents or the fucking army to seize ballot boxes this November, will that make us more safe?

Safety as mirage, as tom foolery, as deceit, as authoritarian tool.

It’s been a decade and a half since I talked the girls through my lessons from Silence of the Lambs. They have solid gut feelings they rely on. They have to, a woman who works for David was assaulted this week by a group of men in Central Park. In the middle of afternoon. Broad daylight, middle of the week. And then, there are the reminders of the Epstein files, forcing us to question what safety can be, when left in the hands of powerful men. I don’t blame anyone who listens to their gut. The world is fuck-all.

But we also have to ask ourselves to move outside of some of the things that scare us. To fight. To be heard. To be cover for other people. To live dangerously, as safely as we can. To stretch outside of things that keep us comfortable. To help the stranger with the couch, without backing ourselves into the van. To find that path that feels dangerous enough. And safe enough.

This will be the thing that sets us free, even if it terrifies us to do it.

_________________

Thank you, as always, for reading. xo Kim

Child of addicts & former foster parent here (I beat the odds!) and I felt this article very deeply. Thank you. I am also reflecting on the role that I am unintentionally playing as a white woman in propping up both white supremacy & patriarchy; the axis of the evil that is on full display right now in our country. Thank you for so beautifully articulating the fuckery that is this political power play, and for (always) using your platform to speak these uncomfortable truths. Every little bit of this kind of media will help tear this shit down.

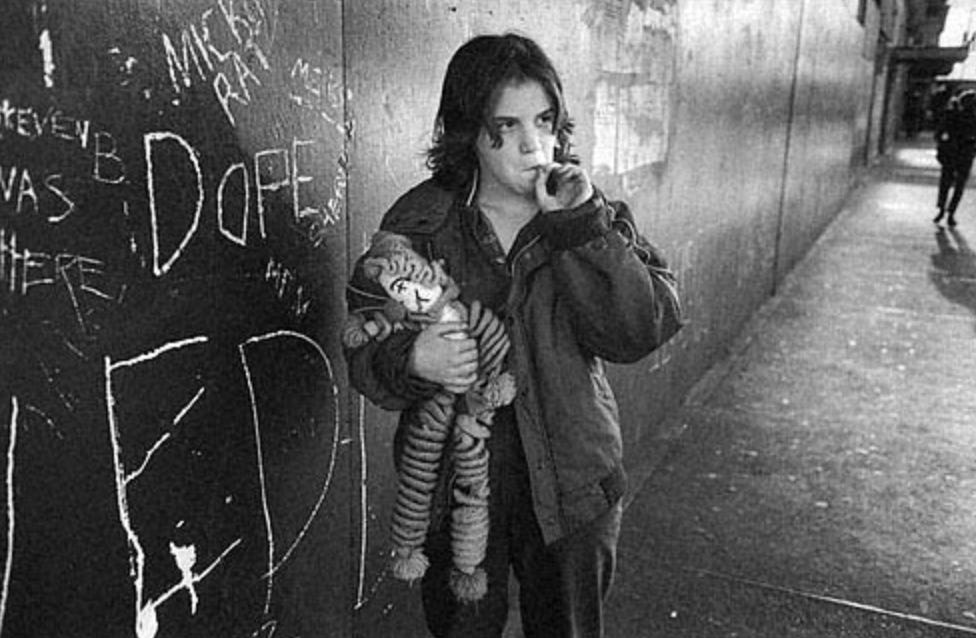

As a young person in 2000, I got to help put up Mary Ellen Mark's 25 Years show, and meet her. She was one of my first in-person examples of a working artist who was doing street photography and staying connected over time with the very real humans in so many of her photos. Some of the images of Tiny, Mike and Rat, the drag queens she captured behind the show, are *seared* in my memory. I wish I remembered the lecture she gave. (I just noticed that there's a Criterion collection documentary about Tiny's life that came out in 2016 - going to add to my list.)