Cages.

Is it finally time to re-imagine mental health treatment + involuntary commitment?

__________________

I’ve been committed to a psych ward three times - and it never helped. For those of us living with severe mental illness, the world is full of cages.

— Esme Weijun Wang, The Collected Schizophrenias

__________________

The death of the Reiners this week has pried open a centuries-long discussion of how we handle the most dysfunctional, ill and vulnerable people in our society.

I wrote this on my socials:

Holding space tonight for the parents in my communities who have chronically mentally ill, traumatized or violent adult children, in or not in, active addiction, who fear they could end up like the Reiners.

I speak to these familes often. There is great shame, secrecy, fear and a worry that all their love - the unconditional love, the tough love - the resources, experts, psych admits, rehabs, treatment centers, police calls, will all be in vain. I’ve sat with them while their kids are doing well and they worry it will be short-lived. And when their kids are breaking down their doors. They never can let their heart rest. They worry that the anger, irrationality and violence they manage, will end in a tragic event just like this.

Often they aren’t even fearing for themselves, just thinking about what will happen to their children after one misguided, unimaginable act of dysregulation. The Reiners were not alone. There are a lot of parents who are afraid of, and for, their children. Every family, in every socio-economic class needs affordable, physical and mental healthcare so they can be as healthy and well, as they can be.

Let’s give that to ourselves as a gift, America.

We have been touched a bit by this, but not nearly as much as the Reiners and other families, gratefully. But enough to understand a bit of the vulnerability, saddness and exhaustion. Enough to know it happens despite socio-economic status, intentions, or parenting philosophies. Enough to know that the minute you try to hide the problem, the shame and secrecy creep in. Why our family? What did we do wrong? What will people think of us? Are we the only ones? Did we make this happen? Are we bad parents?

Sometimes the bad advice from concerned friends - although well-intended - hurts the most. If you just gave him more structure. You don’t punish him enough. That kid needs a good ass whoopin’. I’d take every bit of his stuff away and leave him with a matress and a sheet. They don’t realize that by the time we let them in, we’ve already tried 1,000 different remedies, read 1,0000 different books, uttered 1,000 different pleas to the universe, talked to 1,000 different professionals, cried 1,000 tears behind a locked bathroom door, tried 1,000 different moves to help right our ailing child.

To have an out-of-control child is to have an out-of-control life. The old adage is true: You are only as happy as your unhappiest child.

Our oldest daughter, Lucy, had a psychotic episode during the pandemic. She spent her 16th birthday in a psych ward. She was diagnosed with bipolar. We didn’t know how it might impact the rest of her life, and our lives. But we got a glimpse of what could happen when our child was curled up on the bathroom floor, trying to hide from the aliens. And there’s our son Raffi who came to us from foster care as a broken little boy, who then grew into a raging, aggressive, much stronger boy, who threatened me, barricaded me inside rooms, punched walls, kicked down doors, lied, stole and vandalized. The police brought him home regularly. He fought is way out of several schools. His therapist stopped working with him because she was afraid of him. Our primary parenting goal, for many years, was to love him and keep him out of jail. And there’s our youngest Desi, who can clear a room with her autistic meltdowns. Whole book shelves on the floor. We used to joke that we could never keep dining room chairs because she was always throwing them and breaking them into pieces. Even yesterday, she was hitting me. Dysregulated. Angry. Over and over, hitting me with her little fists. She smashed a dish on the floor. Later, I held her and we cried.

It would be easy to never talk about these aspects of our lives as a way to “protect” our children and their privacy. Some people believe only certain people have the right to tell a story. But stories happen from all angles. And if we live in silos, we wither. If we keep secrets, we keep the shame too, and a debilitating myth that we are alone in the world. There is no shame in struggling, or being in crisis, or having trouble staying emotionally regulated. There is no shame in having a meltdown in the cereal aisle of the supermarket, or a scary mental health diagnosis or a panic attack on a busy city street.

There is no shame for our struggling kids either, especially for them.

The shame is in how we take care of the most vulnerable people in our communities.

The ones I wrote about in The Meth Lunches. The ones with a bigger load to carry. Lots of ACEs (Adverse Childhood Experiences), tough mental illnesses, substance use disorders, profound cognitive issues, traumatic brain injuries. The ones who have anti-social behaviors, who are violent, aggressive, untrustworthy, manipulative, prone to breaking and disrupting things, stealing, and lying. The ones who are terminally impulsive, who seem to have lost their empathy and their compass?

And mostly, what do we do when these inconvenient people are our children, who we love more than our own lives? Have invested deeply in their success as humans? What becomes of us and our families when one of our own slips off the edge of the sane world and becomes dangerous, a predator even? How do we protect someone that we need to be protected from?

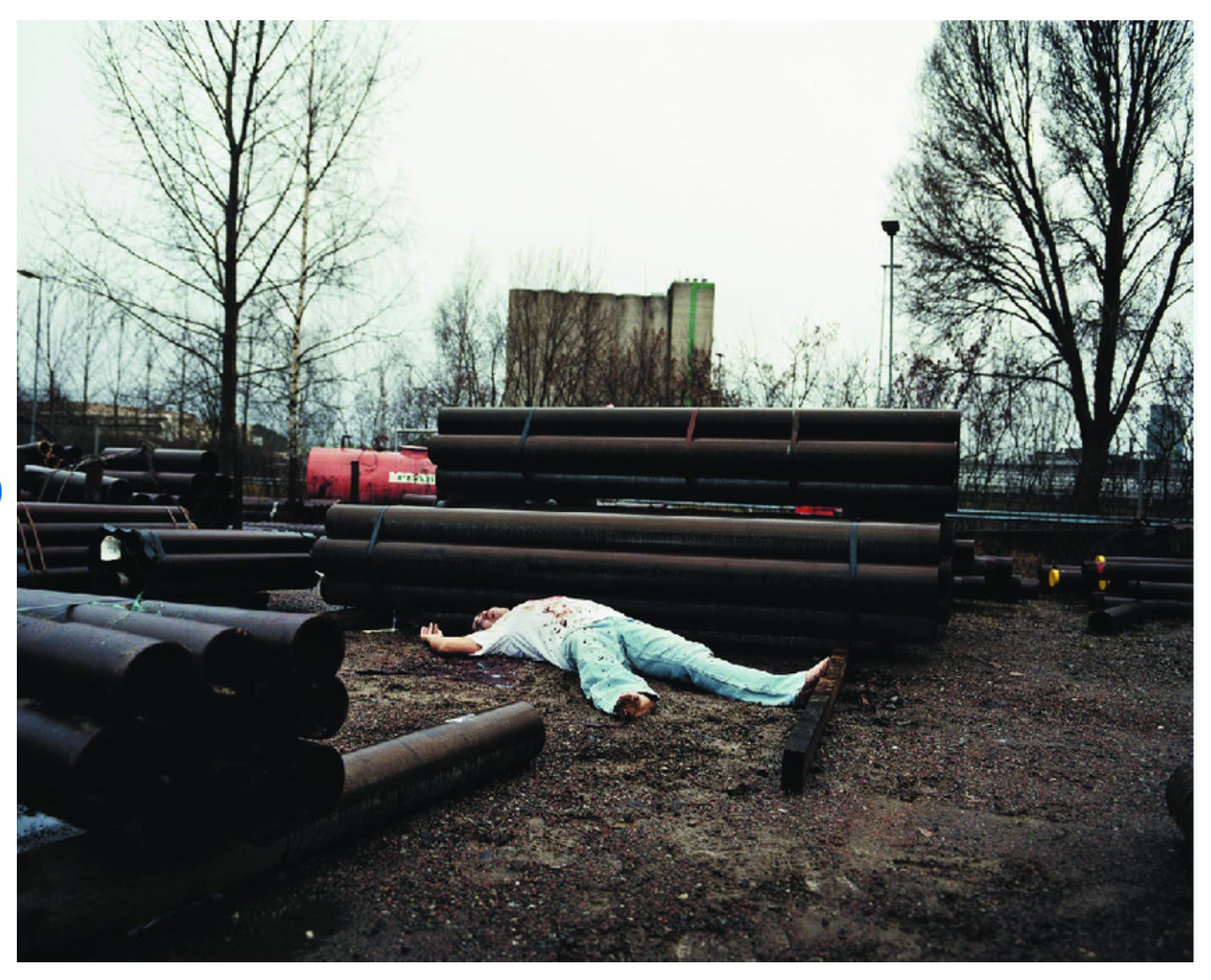

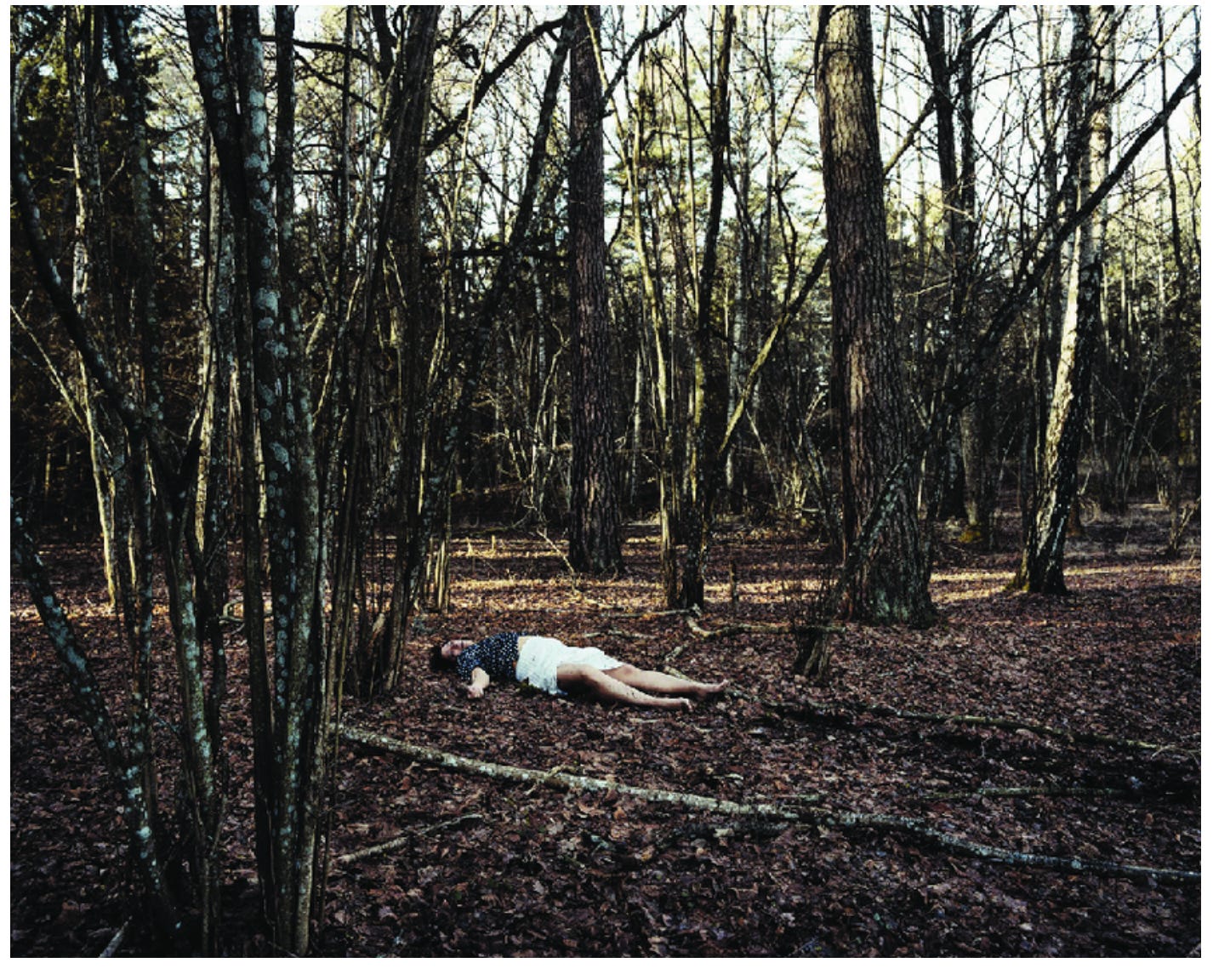

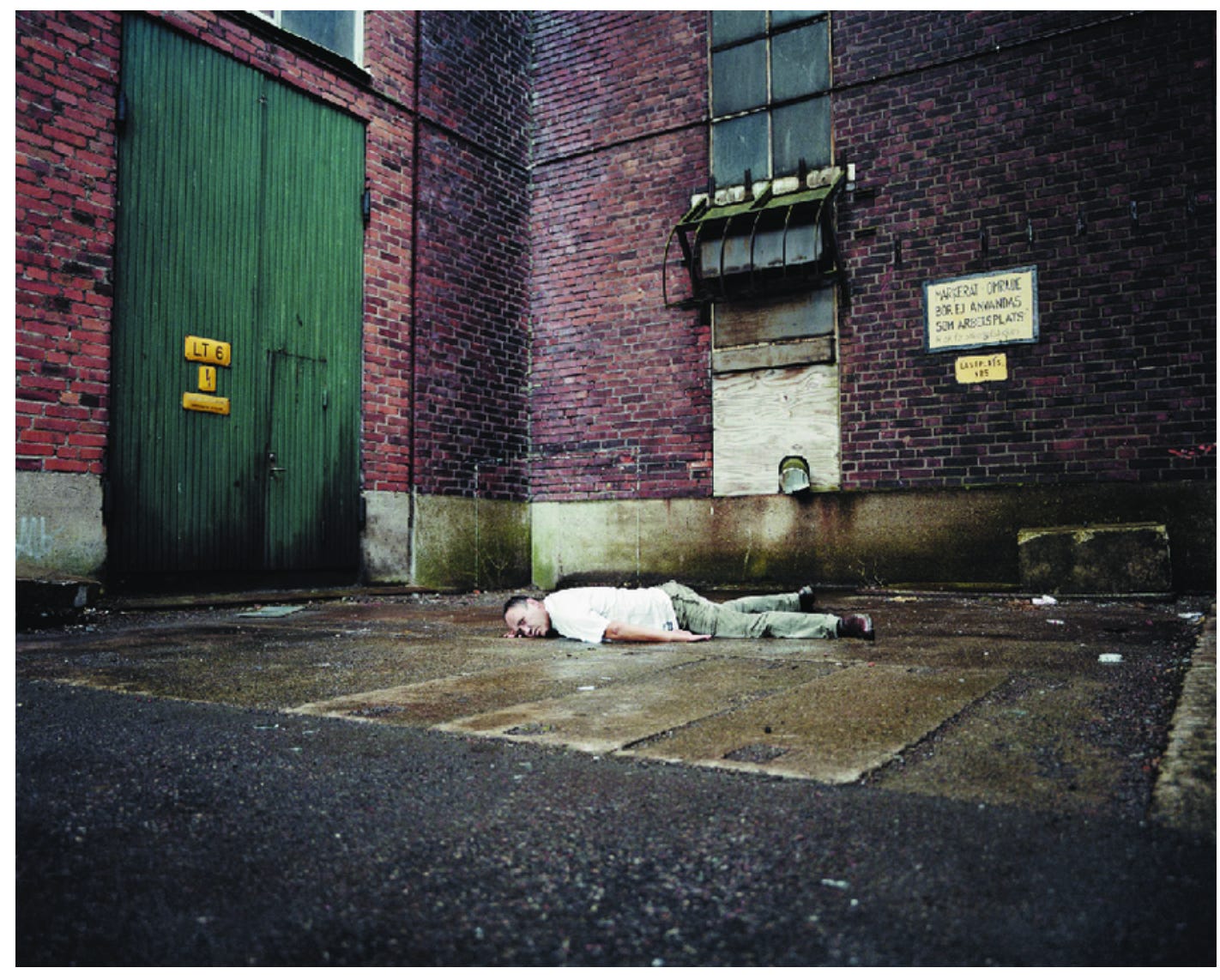

Of course, we aren’t going back to the old systems of warehousing people in institutions. The US has a track record for producing miserable sub-human asylums, and a failure to create a functional mental health system that can support all of our vulnerable people. We have abandoned people in crisis to live in parks, alleys, encampments and subway terminals. We have abandoned them to the elements. To jails. To ERs. To the outskirts of our communities. To persistent struggle. To near-invisibility.

But what happens when the very illness someone has, keeps them from seeking out help and support? What do we do about our most treatment-resistant folks? Is civil commitment - the court-ordered process of putting someone in an institution involuntarily - a viable option?

I didn’t think so. But Italy has been making me re-think.

Italy is considered to have one of the most humane and functional mental health projects in the world, and what drives it is pretty remarkable.

The Americans see involuntary commitment as something that happens when a person is a danger to themselves or others. And the bar is high. They have to be very homicidal or suicidal. Italians do not connect mental illness to violence. Italians have re-framed what involuntary commitment means. It’s brilliant. For them, the standard is whether the person has a “need for treatment”not whether they are dangerous. This means a patient can be considered for civil commitment if they have “severe mental alterations needing urgent treatment, they refuse care, or they cannot receive adequate care outside a psychiatric hospital. This focuses the standard of care primarily on clinical need, not just dangerousness.” This also applies to substance use disorder treatment, when there is significant accompanying mental illness, because Italians “priortize mental health criteria over mere substance abuse.”

The Italians fortified their country with lots of locally-based mental healthcare clinics that are funded through the government and are low or no- cost to the patient. They have free psychological care on offer for everyone. They offer cash annually so citizens can access private, psychological care as needed, since the system can be slow. They have ample psych beds that are available and free. These factors alone contribute to fewer Italians needing involuntary committments. There is a real focus in Italy around never getting to the civil committment stage.

But if civil committment becomes an issue, there is a rigorous review process where multiple people (family, doctors, government officials) have to provide significant documentation about their person’s state of mind. This person always has the right to an attorney, appeals and reviews. Less restrictive options are tried first, with involuntary care as a last resort option only, and there is a real focus on making sure this person is treated with respect and dignity. There are always options to change an involuntary commitment to voluntary. There is a door that leads out of the psych ward.

The system in Italy is not perfect, of course. Services can be slow and they still use restraints in psych hospitals, which has been controversial. But in general, the model holds. Patients who are involuntarily commited to psych hospitals in Italy are allowed freedom within the facility. The facilities themselves tend to be well-run and clean, managed well. All patients have the protected right to communicate with family and friends. When a patient is deemed able to be in the outside world again, they are connected to a health center in their community, receive continued psych services and med support, and can go into smaller step-up houses with daily living and med support, while living inside their communities.

Creating a better and more humane psychiatric system for our most vulnerable people is going to be defined not only by what we say on podiums and in op-eds, but mostly by what we put on the ground. It all comes down to those high quality, functional, accessible, low-barrier mental health clinics, so that involuntary commitment is remote. So we can catch people before they kill their beloved parents. So that 300 people, who are all someone’s beloved child, won’t die in the Mojave summer heat next year.

The Trump administration, not surprisingly, has taken an interest in committing people to institutions involuntarily. Trump signed an executive order in July hoping to expand the parameters of civil commitment. Trump is looking to target the unhoused and people in active addiction, as a way to keep the public order, to be seen as tough on crime, to be the law and order president. Essentially to sweep the homeless and sick into under-funded Alligator Alcatraz’s and most likely without due process. Utah, I hear, is interested in leading the way. The goal is to make people disappear and he is banking on us not caring.

Make no mistake, this is not Italy.

It is a crime that in my city, Las Vegas, the largest single mental health facility is considered to be the Clark County Detention Center. Jail. And yet, we believe the very idea of civil committment is a bridge too far. Maybe it is right now - we lack Italy’s infrastructure, their care and thoughtfulness for people in crisis, their vision for what could be. I certainly wouldn’t trust the Trump administration, or the state of Utah, to roll this out. But are we not imaginative enough to conjure up a system for the US, for our state, that could change people’s lives in real and meaningful ways? Or should we continue to run people through the same-old, dysfunctional grinder; on and off meds, in and out of wards, through expensive, fractured, elusive services with varied levels of quality, where we ultimately abandon them to live in the drug-infested flood tunnels underneath the Strip?

We can do better. We have to.

David and I count ourselves lucky. Our family is doing well. (Knock on wood)

Lucy is no longer considered bipolar, is off her meds and is emotionally stable, going to college and working for David’s shows. I can’t really explain what happened. But maybe mental illness is more fluid than we thought. This New Yorker piece, Mary Had Schizophrenia - And Then She Didn’t connects autoimmune disease with mental health. Lucy is a reminder to me of how little we really know about mental illness and our brains and our resilience

Raffi is 14 now and his brain has matured in ways we could never have predicted. He is learning to regulate and control his emotions. He is off meds. He never hits me or gets aggressive, in fact, he reminds me to stay calm. When he is dysregulated, we help him regulate by co-regulating alongside him. He has sweet friends. He loves building and tinkering with cars and is hoping to go to an automotive highschool next year. It’s a fucking miracle every God-damned day that he is such a joy to be near. I do not know how we got so fortunate. Raffi reminds me that we are all works-in-progress and there is always hope. He is my inspiration.

Desi is 10, our baby. The more we get to know her and learn about her anxiety-based autism (PDA), the more we’ve come to realize that her mom, Kristina, who overdosed on morphine when she was 27, probably had the same undiagnosed and unsupported autism. Kristina’s chronic anxiety, meltdowns and aggression were seen by her family as tantrums, entitlement, wildness and deviance. She was the black sheep. She dropped out of school in junior high. (Desi has never been able to attend school) The more Kristina lost control of her kids in the system, the more she spiraled, the more drugs and booze she took. By the time, she was pregnant with Desi she was drinking and shooting up heavily. She could no longer control it. It ate her alive.

David and I wonder aloud if Kristina did heroin to calm down her heightened anxiety, her screaming nervous system? Was she self-medicating? What would her life have been like if she had a correct diagnosis and solid mental health support? Would Desi and Raffi have their mom now? Would their family be in tact? How many families do we let be destroyed before we make all our healthcare a prioity? Desi reminds me that we can change generational legacies.

It is beyond rotten that rich, successful, talented, beloved American parents couldn’t save their sick adult child. And ultimately, couldn’t save themselves. The Reiners have my deepest sympathies. If they couldn’t do it, how will the rest of us do it?

I’m not the smartest person in the room. I don’t know how to fix this system. But it can be done, because other people are doing it. It doesn’t have to be about cages. We just have to give a shit about people in crisis.

The question is, do we?

Thank you, as always, for reading. Kim xo

____________________

END NOTES:

Hi everyone - I left a little video down below. I will be back with a new essay January 15th. I’ll be finishing up a new book proposal over the break and I also am thinking of new things to do for this newsletter. Feel free to let me know if there are things you’d like to read and see and do here. Open to it all.

Thank you for showing up, reading, and giving me lots of reasons to hope 2026 will be a year of growth and goodness. I hope you have whatever the best holiday means to you. xo Kim

Best piece of post-Reiner writing I’ve read. Have a wonderful holiday and good luck with your book proposal.

I hope 2026 exceeds your highest expectations.

This is such a powerful critic of where "we" are as a nation. Your writing is both "visiting the library" and "having a cozy coffee with a friend." And you embracing 60 is such a beautiful thing!❤️ Love you 😘